An interview with Butch Ulmer

If you’re reading this magazine, there’s a good chance you’ve sailed on a boat with sails built by the company known today as UK Sailmakers. Founded in 1946 in City Island, New York by Charles “Buster” Ulmer as Charles Ulmer, Inc., UK Sailmakers is one of the world’s oldest groups of sail lofts.

We had the pleasure of sitting down with Charles “Butch” Ulmer to discuss his father’s founding of the company that bears his name, and its evolution. This interview will be in two parts.

WindCheck: Was your Dad a sailmaker from the get go?

Butch Ulmer: Well, as long as I can remember, yes. Dad was one of the head guys at Ratsey & Lapthorn in City Island. He was exactly the same age as Ernest Ratsey who was Colin’s father, and they were very, very close friends. He had a little disagreement with George Ratsey, the father, so he left to go work for Fuller Sails. Fuller was a pretty good sized New York sailmaker, who built the building at City Island where the Ulmer loft was. They did a lot of war work during the second World War. They built a lot of things like gun covers, trap work, things like that for the Navy ships.

Dad ended up as a partner with Gunner Valentine, an old Norwegian who ran another City Island loft called Valentine Sails. Gunner Valentine had been a sailmaker on square riggers, and the Valentine family had a loft for a number of years on City Island. But in 1945, the loft caught on fire. My grandfather was a fireman, and he took me through the loft afterwards. I remember walking through the burned out building. In fact, if you go into the building now and look in some of the places, there’s still charred wood in there.

But it was built as a loft, so my father got some investors and my mother had been Henry Nevins’ private secretary at Nevins Yacht Yard [the builder of America’s Cup defender

Columbia and yacht Brilliant). And so in 1946 they started in business. My father was a Star sailor, and he had been head cutter over at Ratsey’s, which was basically the person who shaped the sails in those days, all by eyeball. They started by making one-design sails. There was a Star fleet in City Island, and Snipes, Lightnings and Comets too. They were all very popular one-design classes, so he was pretty successful right from the start.

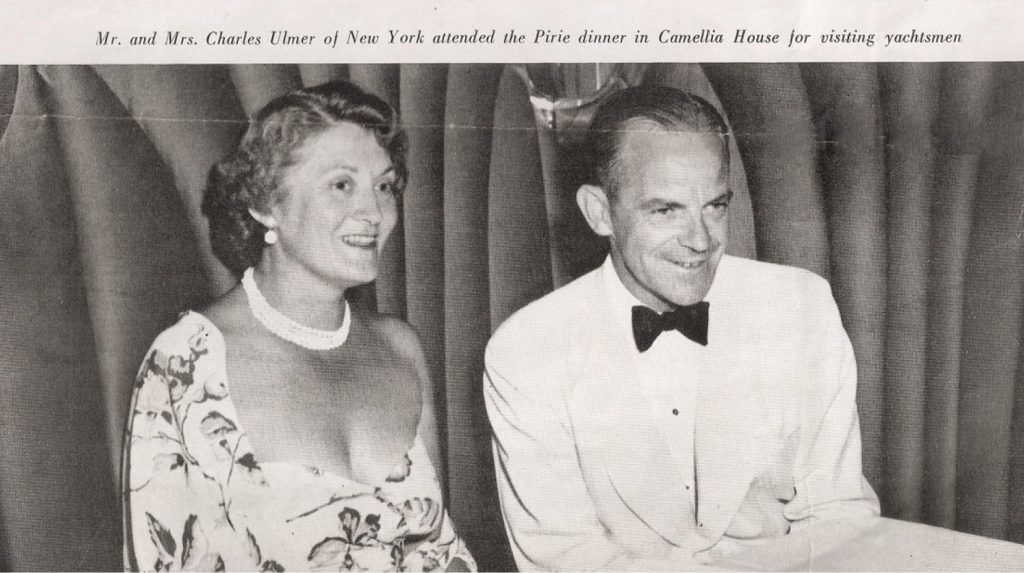

Charles “Buster” Ulmer opened his loft with his wife Charlotte in 1946.

WC: Was Ratsey’s not focused on small boat sails at the time?

BU: At that time Ratsey was the largest sailmaker in the world…that loft was huge! They made J Boat sails there, and this was when the panel width was maybe a little over a foot. And they were all hand-sewn. That’s a long run, and and that’s why there were no left-handed sailmakers ‘cause all the needles had to go in one direction.

WC: Can you explain that?

BU: Sure. I was working for the loft in the summer during high school. So, you would thread a needle and when you did you you got as much thread on it as you could so you didn’t have to do it again for a while. They would have the material running across their lap and they would sew it. The sailmaker’s left hand had the palm on it and the right hand holding the needle would go out to the right as far as the sailmaker’s arm could go, and it had a needle on the end, so if there was somebody over to the right, if you had a left-handed sailmaker, the guy on the left got jabbed. Didn’t work! At one point, a guy who owned a schooner came in and ordered sails. He wanted them hand sewn – not just the finishing but also the seams. They were Dacron sails, but my father sewed them for him by hand.

WC: Before your dad left Ratsey, we hear he made sails for some pretty important boats.

BU: Well, yeah. I mean, you have to understand that Ratsey was the largest sailmaker in the world by far. Dad was likely the lead sailmaker for Ranger. The loft employed well over 100 people. Yeah, it was a big business. City Island in those days was just boat businesses. You had Henry Nevins, who was the premiere boat builder in the world. This was right after the war, so there were no European boatbuilders to speak of because they had all been flattened by the war. And the sport was pretty confined to wealthy people. I was at Bolero’s launching as a kid because my mother was Henry Nevins’ secretary as I said.

WC: So, your dad took advantage of a market opportunity with the smaller one-design boats that Ratsey probably might not be bothered with.

BU: That’s certainly a possibility. When you start in business you’re looking for any opportunity you can find. My parents were both very hard workers. My father worked as a butcher on Saturday mornings while working at Ratsey’s, and he used to say he made more money Saturday morning than he did the whole week at Ratsey’s. There was no family wealth, if you will. What they had they made. So if you had an opportunity to do some business, you took it. There probably weren’t many sailmakers for those smaller boats in those days, but they were getting more popular for sure.

I don’t know exactly when the sewing machine came into being, but I know the Star sails were hand-roped. They moved the draft around in the sail itself with tension in the ropes.

It was probably something that Ratsey didn’t want to bother with, so it was a good way for Dad to number one, make a living and number two, make a reputation, and he was successful at both.

For the materials? I mean, this was a big part of sails. In those days you had to go out and break them in. If you bought a new sail you wanted it to stretch into shape properly, so you didn’t go out for the first time on a real windy day. It was part of the process. I’m not sure how much was lore and how much was fact ,but nonetheless it was the way you did things. And it gave the sailmaker the ability to say, “Well, you didn’t break it in properly!”

WC: How big was the loft back then?

BU: It probably had 20 or 25 people, because there was much more labor and all the work was done by hand. When you put a ring in the sail it was hand-sewn, and when you put a boltrope on it, it was hand-sewn. They used to finish off three-strand rope with what they called the rat’s tail. They would taper down the end of each strand and then twine it back together and hand sew it down. Typically that would go around the headboard and down the leach a little bit. Then we’d go all the way down the luff, across the foot and back up the leach a bit. You needed a staff of handworkers who could just do that, and there were five or six of them in my father’s loft.

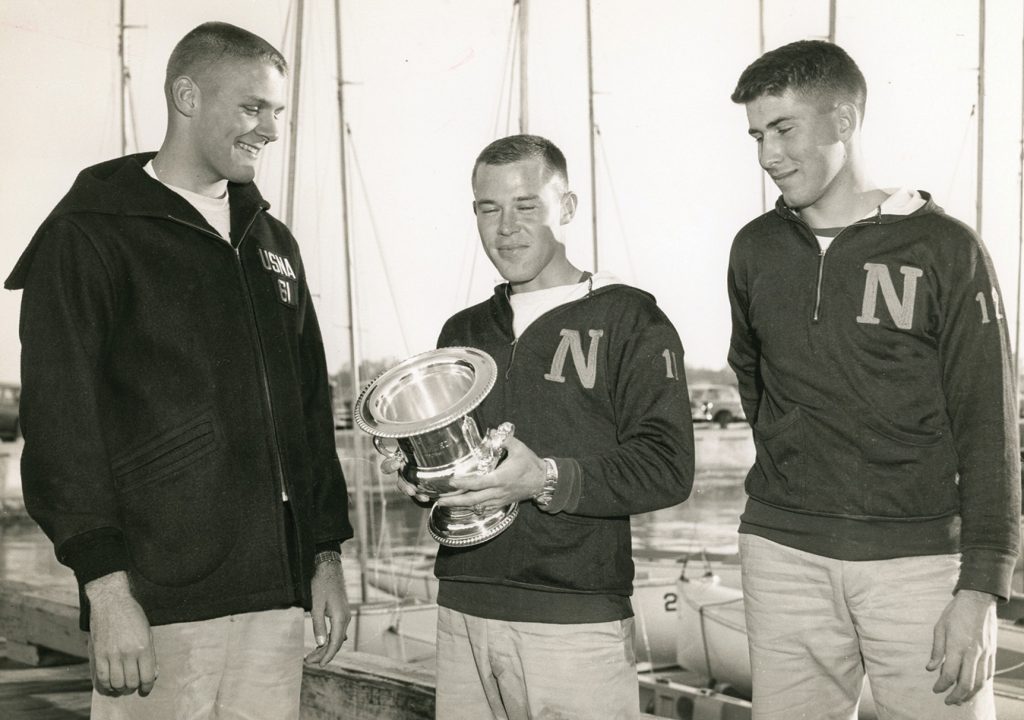

Charles “Butch” Ulmer (left) with U.S. Naval Academy Sailing Squadron teammates Ed Lutz, and Jim Sand, early 1960.

WC: Was the handwork done with cotton thread?

BU: Yes, and the bolts were tarred hemp.

WC: Was it hard to manage the stretch characteristics of hemp versus cotton?

BU: Of course, but most of those masts had grooves, so the boltrope served as the primary structural member of the sail. They would mark the rope very carefully so you would know how much cloth they gathered here as opposed to how much cloth they gathered there which impacted the draft of the sail. But there was an awful lot of trial and error…luck! Pull more of the cloth into one area than another area because that area would have more load on it so it would stretch more, and it was designed to help control the position of the draft.

They were beautiful sails when you got them up, because all the cotton would stretch and they were just as smooth as they could be. So if the draft was correct as far as the spar bend and bend of the boom, they were absolutely beautiful sails that really worked. Not a wrinkle in them because of the cotton. But it was very much an art as opposed to being a science.

In 1953, we went to Italy on the Andrea Doria for the World Championships in the Star Class. It was in the Bay of Naples. The Star boat was deck cargo and we went with a couple Cubans, the Cárdenas family, both of whom subsequently became Star World Champions, but Dad had the boat filled with Star sails, and when we arrived there were people standing in line to buy them. The Italian money looked like high school diplomas, and when he came back into the hotel he had money coming out every pocket in his pants. It was great!

WC: Do you think that trip paid for itself?

BU: Oh sure, many times over.

WC: Who crewed for your dad on the Star?

BU: I did most of the time. I don’t remember who crewed on that event. I was too young then, but later on I crewed for him in Lisbon, Portugal. The best he did was in an earlier Worlds in Portugal with this guy named Bundy Farrington. He was Durward Knowles’ crew and they had won the Worlds together. So in Lisbon my father got sixth in the world with Bundy in a good event. They had fifty or sixty boats and it was a real world championship.

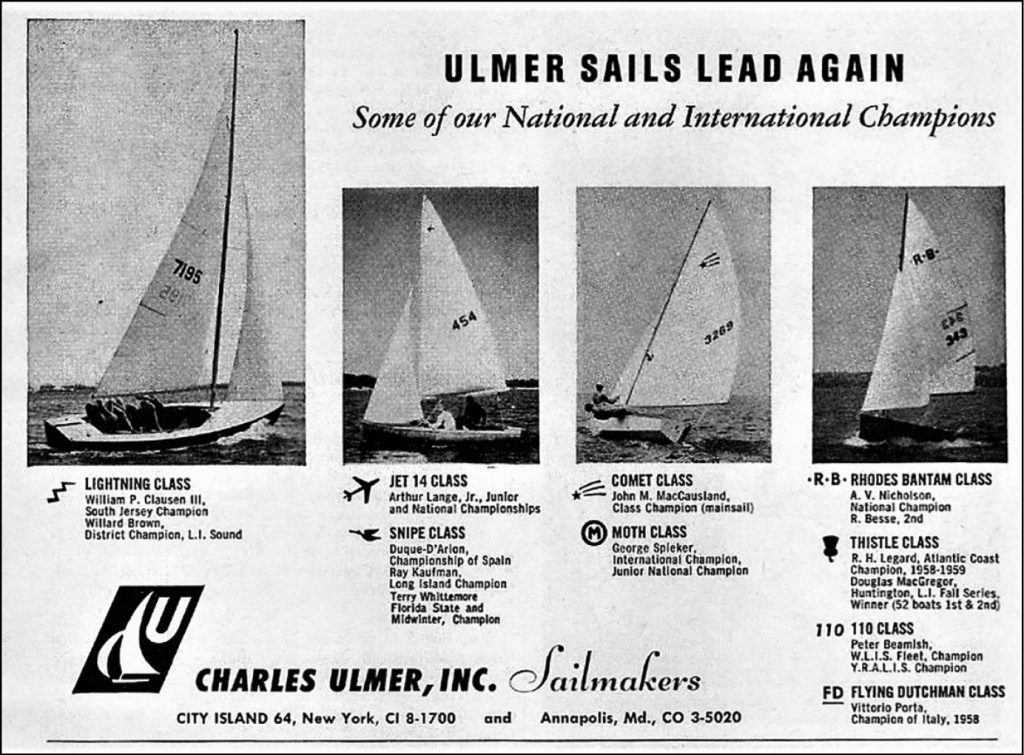

As this ad in the January 1960 edition of Motor Boating indicates, boats with Ulmer Sails ruled the roost in races and regattas around the world.

WC: How did the business evolve from your dad to you?

I left home in July 1957, when I became a midshipman at the Naval Academy, and I was pretty much taken up by Uncle Sam until 1965. I did some sailing because the Navy let me try out for the Pan Am Games in the Finn. I didn’t qualify, but then I did some more sailing and just before I got out I was stationed at Annapolis at the naval station and they put the first fiberglass yawl (Navy Yawl) there and Toby Tobin was the skipper. That was about when my contact with home was getting a little closer, and I had made up my mind that I was going to get out of the Navy and I was going to get married and I was going to join my father. I went to work for him in 1965.

Dad was 65 at the time; he was born in 1900. His battery was wearing down at that point and my brother-in-law, Chuck Wiley, was involved in the business. Chuck was a good sailor and a good salesman, so he was kind of carrying the load when I came along. ■

Look for the next part of this interview in our November/December edition.