Imagine this. You are looking at a boating industry magazine and see an article from the National Marine Manufacturers Association. It reads: “Powerboat sales are still booming in 2021. Retail unit sales of new powerboats in February 2021 were up 34% compared to the same period last year.”

Everyone saw it. No one saw it coming: The Great Powerboat Drought of ’21. In the year of COVID, sales of small boats and engines were off the charts

The last year could have been 1921 all over again. Post pandemic, post war, boating booms. And yes, with The War to End All Wars and the Spanish Flu behind them, boating enthusiasts of the day bought brands like Riva, Hickman, Hacker, and Chris Craft. Compact powerboats flew out of factories to new boating families. It was an era of new materials and new designs. Plywood made its entrance, foreshadowing the arrival of fiberglass. New materials sparked a revolution in design and construction; the Great American Runabout made its debut.

It had only been 50 years earlier that a short, intense MIT engineer joined his family company. With steam engine experience, he jumped in to help his blind brother meet the demands of the early Gilded Age customers for launches and tenders for their larger and larger yachts. He was to become the most important designer at the turn of the 20th century. He was Nat Herreshoff.

Herreshoff, the Steam Launch and their Gilded Age Masters

In July 2021, during the Herreshoff Marine Museum’s (HMM) Jubilee Celebration, I returned to tour the redesigned museum. The new footprint started with the story of Herreshoff and power. How many know the Wizard of Bristol had almost as many powerboat designs as sail? Remember that he came from a propulsion, not a boat design, background. Out of MIT in 1874, Nat went to work for the Corliss Engine Company. It was firms like Corliss that built the steam engines, large and compact, coal-fired, that ran the mills and factories of New England. When you visit the Rossi Building at Mystic Seaport Museum, you almost trip on the rows of old smallish steam engines. To my eye, they look like the droids in a Star Wars movie, long silenced from their former roles making American factories whir.

Although petroleum was on its way in at the end of the 19th century, coal was king and coal made steam and steam drove boats. In their early years, yacht clubs were canoe clubs or coal yards masquerading as boat clubs. I think of elegant clubs like Nantucket yacht Club: Immaculate white clubhouses, coal yard next door. Glamorous? No. The reality of steam? Absolutely.

It was in the powerboat sector that Herreshoff refined his concepts of patented design, full integration, and customer service. HMM Curator Evelyn Ansel first educated me on his process expertise back in 2019 in a lecture at Nantucket’s Whaling Museum. Her work demonstrated that his manufacturing systems were the secrets that enabled Herreshoff’s prodigious output and attracted the attention of budding industrialists such as Henry Ford.

Sandy Lee, the mechanical guru of the HMM who gave me my tour of the massive Reliance model five years ago, sums up Capt. Nat’s approach in the introductory video in the HMM’s lobby”

“NGH was not just a designer. He was a manufacturing engineer, with control at the Burnside Street facility of a massive amount of manufacturing resources, for sail and power alike. Power, propulsion was a means to an end: to drive an elegant and efficient Herreshoff hull.”

It is said that Nat had an example of a steam engine installed in the Herreshoff household’s playroom, the better to acquaint the children with the family profession. Much of Herreshoff’s design work on power was for the U.S. Government, from picket to torpedo boats. But ultimately, one customer got his best work.

J.P. Morgan was the Captain of Finance who would bail out the U.S. financial system during the Panic of 1907. He was “Mr. Morgan” to Herreshoff, and his annual visit to Bristol, Rhode Island was an annual event. Repeat customers are important in any business, but none more important than Mr. Morgan.

He bought every year, from tenders to the annual steam launches. For sure, there were quirks behind his purchasing habits. Steam only, please. Why did he demand steam power when Herreshoff’s other customers like Henry Ford were betting the ranch on petrol? The inside joke was that Morgan didn’t want any Rockefeller dipping into Morgan’s pocket for the fuel bills for his boats.

The Herreshoff – Morgan relationship went on for fifty years under the name Corsair. One of the HMM’s unique exhibits is its display of transoms. One from a 30-foot Morgan launch, a tender to the bigger yacht, is a big mahogany oval with bold gold letters.

© Peter Taylor/Mystic Seaport Museum

Other pictures on the main floor and the Model Wall on the second floor show the breadth of the powerboat designs. Some craft seem tiny, tenders to the larger 60-foot plus steam launches. Beginning in the 1880s, the captains of industry used a water-borne vehicle to commute to Wall Street. Herreshoff had the latest models to get them there.

But time would not stand still. The 20th century brought petroleum power and innovative new hull shapes. When Nathanael Herreshoff retired in the 1920s, the writing was on the wall. Steam and lofted half model designing had become things of the past, just as square-rigged ships and wood planking were dated to Nat in the 1870s.

John S. Barry and the Hickman Sea Sled

The story of the Sea Sled is the story of the mystery that lurks behind the design of any watercraft. Boating design is derivative. We call it the use of the “Traditional.” In the 20th century, the terminology for design and innovation that is unique and revolutionary was “IP” or Intellectual property. What’s the IP of a boat? Is it in the mechanics or the shape? Can you patent a shape?

© Peter Taylor/Mystic Seaport Museum

Herreshoff wrestled with this in his patent filings, for radical craft like the catamaran Amaryllis, but he had all the minute details of his designs in his brown books, including the all-important offsets and building details. And he had the half models.

Olin Stephens parted with his drawings only under extreme duress. His refiguring of the famous Six Metre Goose showed that. In 1938, when George Nichols wanted to use a yard owned by a competing designer, Luders, Stephens refused to supply the plans.

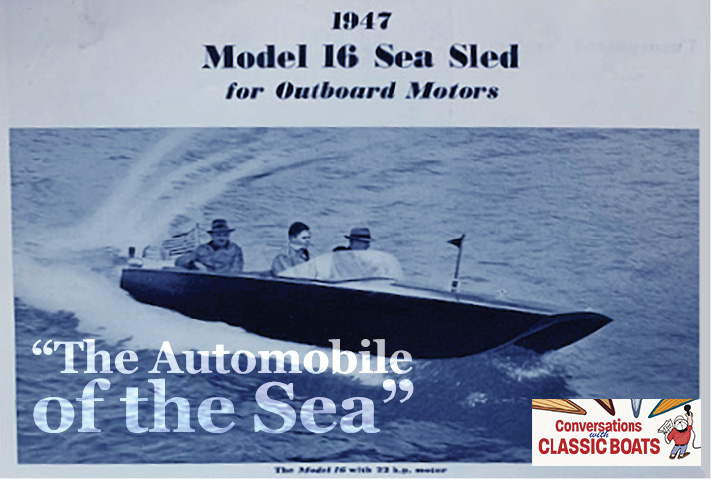

In 1914, an eccentric Canadian boat designer name William Albert Hickman came up with a design so iconic that it was being imitated by one of America’s great designers almost two generations later. From the day of its introduction, the Hickman Sea Sled was a classic design. It was a 1914 issue of Scientific American that described the details of the Sea Sled:

In the W. Blunt White Library at Mystic, the John S. Barry Papers, 1940-1976, in the collection of the Chief Designer of the Hickman Sea Sled Company, 201 Devonshire Street, Boston, John S. Barry documented this iconic twin hull design from 13-foot runabout to 200-foot naval warship. The original Sea Sled had a twin hull configuration and an inboard gasoline engine driving the original version of what we would call today a “stern drive,” with propellers right at the waterline. Made of plywood, a new innovation being promoted by the Canadian timber industry, the Sea Sled was the choice before World War I of the U.S. government for a fast motorboat design.

In September 1914, a 54-foot Sea Sled design, with an internal steel frame, four of his “surface piercing” propellers, a single 18-inch torpedo and a 3-pound Hotchkiss gun was proposed to the U.S. Navy as the first high speed motor torpedo boat, forerunner of the World War II PT Boat.

They were built until 1919 but not before this model topped 37 mph and sustained speeds of 34.5 knots in a wintry nor’easter with 12- to 14-foot seas.

In the 1920s, Hickman rolled out a line of runabouts from 13 to 40 feet. In the marketing literature in the Hickman archives, publications like “A Revolution in Fast Motorboats,” written by Hickman himself, sang the praises of the Sea Sled:

“Quite recently two engineering developments have made it commercially possible for this most radical small vessel to dominate the field of fast motorboats. One of these is the quantity of good high-powered lightweight automotive-type marine motors with geared down propeller shaft speeds: the other is the perfecting of dependable waterproof bonded plywood.”

“Because the Sea Sled, compared with the older round-bottomed or V-bottom craft, has an enormously greater weight-carrying capacity for a given power and speed, it is now possible to have easy-riding motorboats that run, in many cases, almost twice as fast as the old models with the same fuel consumption per mile, and can run at speed in a sea condition impossible for the older types.”

Seeing himself as Henry Ford on Water, Hickman’s ads trumpeted the Sea Sled as “The Automobile of the Sea.”

Mystic Seaport Museum Archives

He went on to say, “No application of the V-bottom would be successful…to carry substantial useful loads and to maintain speed in rough water.” Hickman would live to regret that statement, and Ray Hunt would prove him wrong in 1957.

Hickman had gotten one thing right. The twin hull was the basis for the future. That design would come to life in 1957 in the hands of a backyard entrepreneur and one of America’s great designers.

The Sea Sled and the Whaler

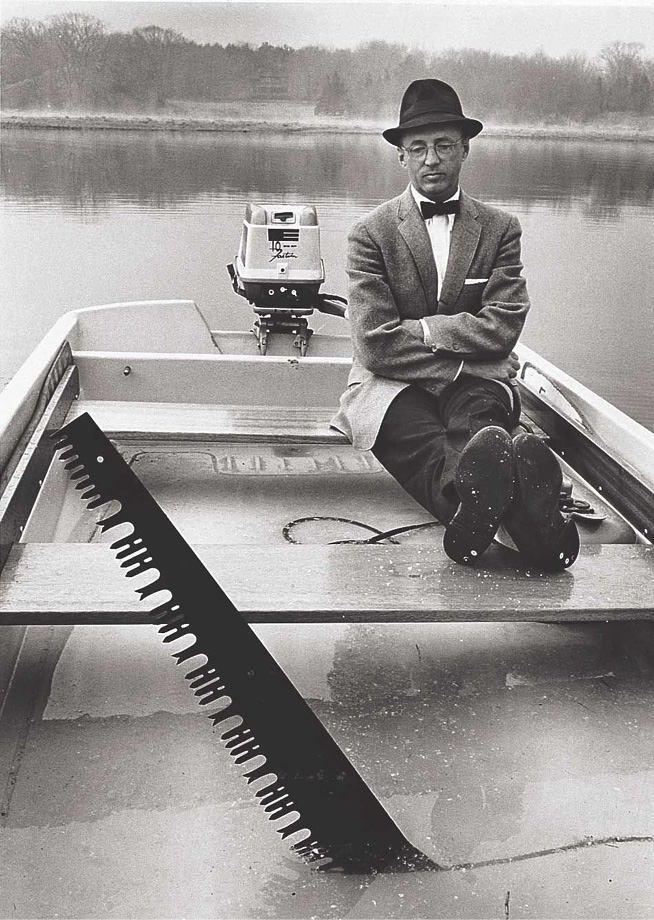

Conversations with Classic Boats podcast listeners have heard me describe Mystic Seaport Museum’s Rossi Warehouse as the Old Curiosity Shop of vintage small boats. On entering, one goes past the miniature steam engines, then left. There, sitting inclined at 45 degrees is a dark mahogany-decked plywood runabout. Directly to the right, one spies the quintessential aqua interior of a cathedral-hulled, undecked fiberglass runabout. The first is the Sea Sled. The second cannot be mistaken. It is the 13-foot Boston Whaler.

And next to those two is a poster of one of the greatest examples of American consumer marketing, a display ad with a man in a suit sitting in the aft section of the Boston Whaler while a menacing timber saw cuts the Whaler in half. It is the equivalent of the magician sawing the lady in the box in two. In the late 1950s, this ad read to the boating consumer as “Cool.” And it said to all the parents who bought their kid a Whaler, “Unsinkable.”

A 1950s ad for the Unsinkable Boston Whaler

This icon of American outboard powered craft was the – directly or indirectly, you decide – the work of one of the design iconoclasts of the 20th century, the Herreshoff of the powerboat hull, Ray Hunt.

Born in 1908, same as Olin Stephens, Ray Hunt was one of the more unusual characters that grew up in the boating industry in the post-WWII era. His life story starts with youth on the South Shore of Boston, winning the Sears Cup for Duxbury at 15 years old. He had two years of secondary education at Phillips Andover Academy. Like Rod Johnstone of J Boats, he was a self taught designer.

Early in his design career, Hunt penned an idiosyncratic series of sleek, double-ended racing yachts numbering from 110 to 1010. The 210 was the alter ego to fleets like the IOD in Long Island Sound up to New England.

In an August 2020 Soundings article on Hunt, Gary Reich pointed out that the 30-year-old Hunt’s opus “was the Concordia Yawl, splashed in 1938 – a gorgeous, fast and seaworthy passage making sailboat” that came a full fifteen years before Olin Stephens’ Finisterre. There were 103 Concordias built, many at Abeking & Rasmussen near Hamburg. All but a handful are still on the water.

His designs, in sail and power, from the Concordia to the 110 and then in his quest to establish his idea of the Deep Vee hull, the very form that Albert Hickman had dismissed two generations before, speak to his out-of-the-box thinking. Ray Hunt’s design philosophy was “Watch. Think. Draw.” A stint in the Coast Guard during the war formed strong opinions about how to make a powerboat perform in rough conditions. Hunt’s design ideas, from the Ray Hunt Design Group website, include:

“The high deadrise, or Deep V, hull is proven and accepted as the ultimate hull form for speed with comfort and safety in rough water. The sharp entry forward keeps pounding to a minimum. There is no deep forefoot to cause bow steering and broaching…these factors urge the hull to travel straight through and over the seas with only moderate steering effort…”

Several pages later it concluded:

“For all these reasons the Hunt Deep V platform is the best design for speed and good seagoing in rough water.” Over a generation, Ray Hunt changed the design paradigm for open water powerboats.

And what about the Whaler and the Deep V? Where is their intersection? Hunt worked with Dick Fisher and Rob Pierce to conceive the Boston Whaler 13. Fisher wanted to build a very stable boat using foam coring and the new fiberglass. The creation myth of the Whaler has multiple paths. How did it come about?

The first version goes like this: In 1956, Ray Hunt’s friend Dick Fisher came to him with a request. Dick had a prototype in mind for his new design. It was called the Sea Sled. Would Ray talk to Hickman and ask if he could us their design for this new concept? The elder Hickman did not respond to the inquiry. Finally, he said “No.”

Marine functionality and modern design

No record of Hunt’s precise response appears to exist, but the upshot was Hunt took the Sea Sled’s inverted V hull and added a mini hull in the middle creating the cathedral hull associated with so many Whaler models from the 1950s on.

When I look at a Whaler out of the water and up in the air, the elegance and the complexity of the bow curves seem like a design of modern art, by Miro or Picasso or Braque. Given Hunt’s location on the South Coast, east of Newport, west of Woods Hole, it seems unlikely Euro art radicals influenced his work view.

But Hunt’s working style was quite similar. Observation and improvisation followed by dogged defense of the work. The natural curves of the Whaler, and its radical hull design and construction, were the work of a modern artist.

What an irony that Hunt’s greatest contribution to boating, the Deep V, would be overshadowed by the Whaler itself. Ironic that the Whaler itself was, at the very least, a fiberglass and foam adaptation of the WW I vintage Sea Sled.

The Boston Whaler was as iconic a post-war product as there was: a 1955 Ford Thunderbird, a 1954 Hobie surfboard, a 1963 Schwinn Stingray bike. The Whaler is the Model A of the modern American fiberglass runabout. You can have any color hull as long as it’s white, that aqua non-skid finish was as iconic as the Dyer Dhow’s blue interior. It is fitting that, the boat chosen by Mystic Seaport Museum to showcase for its July 2021 Rendezvous was the Boston Whaler. ■

Tom Darling hosts the Conversations with Classic Boats podcast, which is available on Apple Podcast, Google Podcast and Spotify as well as online at conversationswithclassicboats.com. You can also hear episodes via SpinSheet, Scuttlebutt Sailing News, and WindCheck. Community sailing groups such as Sail Newport and New England Science & Sailing also distribute episodes of Conversations with Classic Boats. Tune in to hear Episodes 14 and 15, “Herreshoff, Hickman and Hunt: 100 Years of the American Runabout.”