By Tom Darling, Conversations with Classic Boats

This boating history is one of connecting the dots of boat design over almost a century, with names that are larger than life: Uffa Fox, Bruce Kirby, Dr. Stuart Walker. Their common heritage is small boat performance sailing. As a sailor in Long Island Sound who escaped the slow and steady Blue Jay and Lightning for the speed and trills of the Thistle and the Laser, I can identify. I come from a planing boat family. We have the need for speed.

Uffa Fox and Bruce Kirby: The Flying 14s and the Modern Planing Dinghy

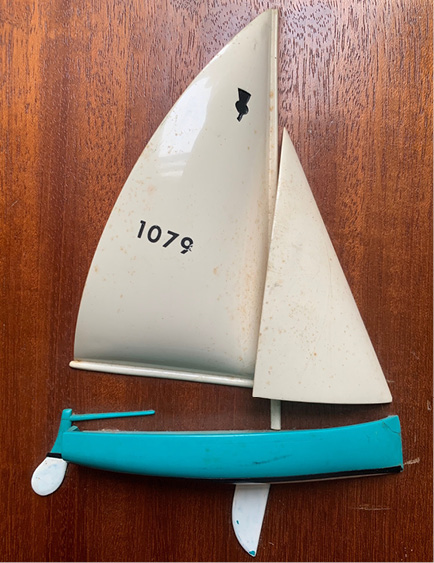

My father built Thistle #1079 from a kit delivered to the driveway of my first house in Huntington, New York. She came out purple, fitting for a Thistle, and was then repainted aqua. She was called Nautigal. I crewed on that boat from early elementary school, and always wondered where the Thistle design came from, and a book from my great uncle, for whom I am named, clarified that. The book was by Uffa Fox, eclectic dinghy designer, sailing personality, crew and sailing instructor to England’s Royal Family. His boats, called Fourteens or International 14s, were the missing link between slow boats with chines and quick boats with curves. The profiles and curves were in the 1920s part of a revolution in small boat design. The boats were called “planing dinghies.”

The 16’ 11” Thistle was designed by Gordon K. (Sandy) Douglass. Thistle #1079, depicted on this 1964 trophy, was built by the

Up in Ottawa, Canada, a polymath teenage sailor turned newspaper cub reporter named Bruce Kirby (a couple of years younger than my father) was pursuing homebuilt designs to a development rule for 14-foot dinghies. Twenty years later, with his first Kirby Mark I, the design that set the pace for this development class for years, Journalist Kirby set off on a path of Boat Designer Kirby. That trip led in the early 1970s to his iconic planing dinghy, the Laser, the boat that put the Baby Boomers on the water.

Fox and Kirby came together in the midst of the development of the granddaddy of planing craft – the International 14. A dedicated group of designers and builders chose the 14 as their testbed for the idea of getting a lightweight, rounded shaped boat to rise up out of the water and accelerate as no craft had before – that suspension of physics and hydrodynamics we call “getting on a plane.” Whether you have sailed a Sunfish, a Laser and any one of dozens of classes, you have Fox and Kirby to thank for the innovation and the experience.

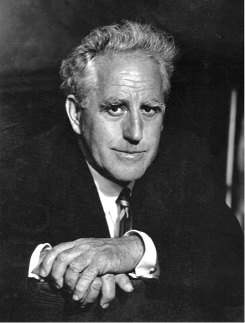

In post World War I England, one Uffa Fox was emerging as the driving force for the dinghy development that started in that same period. His medium was the International 14. One of the great characters in the yachting and yacht design fields, he also designed notable small boat classes including the Flying 15 (where he crewed for Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh in the 1950s), along with the Albacore, Firefly and Jollyboat. For the years leading up to the end of World War II, Uffa Fox was the world’s leading dinghy designer.

The passing of the baton from Fox to other planing boat zealots, the most successful of which was Bruce Kirby, is a story of radical design combined with cutting edge materials. There is a long and venerable lineup of International 14 competitions, from massive fleets of boats in events like the English POW Cup, to intense hand to hand team races in the Western hemisphere in Bermuda and America.. Names like Glen Foster, Colin Ratsey , Dick Carter and the ultimate International 14 man, Dr Stuart Walker, went on to stoke the fire of the 14 phenomenon.

Uffa Fox, the Flying Fox, godfather of the planing dinghy

Another boat design philosopher, Alfie Sanford, godfather of the recreation of a 20th century keelboat classic, the Nantucket Alerion, summarizes the phenomenon of how boat design cycles work to produce breakthrough innovation, here, in the planing dinghy.

In his 2021 book Wooden Boats for Blue Water Sailors, Alfie writes: “A race event, like many human competitions, develops over time in a pattern that is timeless. It begins with pioneers. A few brave and brilliant pioneers establish an idea… The pioneers inspire followers whose money and energy create a flourishing golden age in which the idea and the equipment for pursuing it are perfected…”(Sanford, p19)

The performance dinghy movement was all Uffa, Sanford thought. He continued: “In 1927, England’s irrepressible Uffa Fox upstarted sailboat racing with his invention of the planing dinghy, Avenger. In 1952 he extended the planing concept to keel boats with the Flying Fifteen. The planing boat ignored the demands of seaworthiness and radically increased the upper limit of speed under sail. Unbeatable on protected water, Uffa’s conception won all races. While no one will call planing dinghies comfortable, for short spells, they are great fun and great sport…” (Sanford, p21

I am sure Uffa would have loved to have designed in the cold-molded construction era that Alfie has championed in his keelboat designs. Fox’s boats were meticulously assembled pastiches of woods, held together by glue and varnish; known as “hot-molded” hulls. The building in WWII of the all-plywood, hot-molded British night fighter, the Mosquito, may have done the most to propel dinghy designs toward their optimal construction method. This in turn enabled and accelerated the development of the planing design.

Just look at Fox’s portfolio with the Firefly, Albacore, Swordfish, National 12 and 18 and Jollyboat as the model for American designs like the Jet 14, the Thistle and the Flying Scot. At the same time American designers were tied to their massive J Boats, Fox thought small. His books published through the depths of the Depression were jam-packed with ideas and innovation for the small boat sailor.

Mark Smith, who worked in publishing with Kirby and who edited The Bruce Kirby Story, provided some line drawings of what Alfie is talking about on innovation in planing boats. Drawings of Avenger depict rounded surfaces and long, flat runs aft. This was what gave Fox designs the ability to get up and go downwind.

The Kirby book details that in 1949, Uffa became a friend of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh and they raced together at Cowes Week on many occasions on Fox’s Dragon Fresh Breeze or the Duke’s Bluebottle. He also took the Royal Children sailing. This, despite his reputations for issuing “instructions to the crew in a far bluer language than is considered appropriate for Royal ears…”

(The Bruce Kirby Story, p233)

Bruce, meet Uffa. Uffa, meet Bruce.

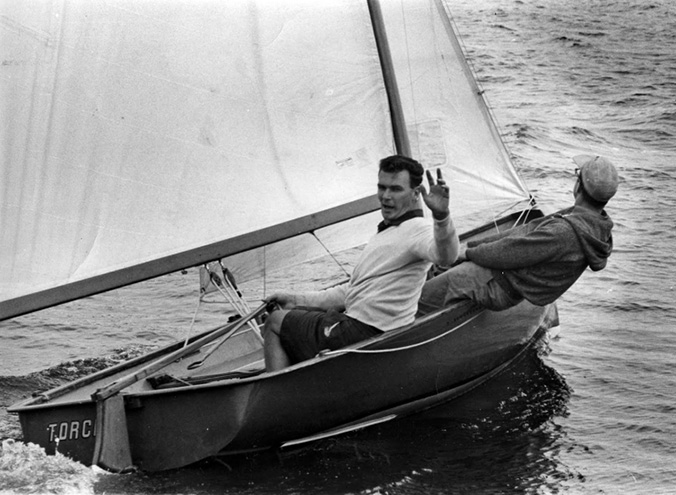

Bruce Kirby (white sweater) launching Torch, the orange Mark I

The two may have first encountered each other in 1958 during an international team race for International 14s in Cowes. Bruce, as we will see, was the self-taught intuitive designer, much like a Rod Johnstone of J Boats or Ray Hunt with the Concordia. His fame came from of a series of International 14s, the muscle car of the dinghy set which in turn led to the introduction of lightweight, powerful trapeze dinghies like the 5O5.

Kirby’s path to the International 14 ran through his sailing on the Ottawa River in Canada. More like a lake than a stream, the river spawned a wide variety of designs from scows to deep keelboats. As a 17-year-old in post-WWII Canada, he admired “the Bourke designed 1933 International 14 Lady Esther…Canada’s first International 14, and Bourke-designed dinghies went on to dominate the class in North America for many years.”

Before and after WWII, Kirby’s local Britannia Boat Club in Ottawa became the hotbed for 14 sailing in Canada. Designers and builders experimented with hot- and cold-molded hull construction, pushing hulls to be lighter and stiffer. Although only a foot longer than Kirby’s ultimate design of the 1970s, the Laser, the 14 hiked helmsman and crew under a massive amount of sail; unlike today, no trapeze.

Kirby had two parallel vocations; journalist by day and night, and amateur racer and designer in his spare time. I can identify, but sailor, writer and journalist? Those are three balls tough to juggle and succeed. My friend from Nantucket, Nat Philbrick, would nod in agreement. He wrote the admiring foreword for Bruce’s memoir.

It was the intersection in 1958 in Cowes with Uffa Fox that pushed Kirby to be a more formal designer. It was that year’s running of the 14s team race event that dated from the 1930s that “propelled a young journalist (he was just 30) into the precarious world of yacht design.” He told the story of the rough and tumble finals between Canada and New Zealand, a sort of demolition derby taken to water. But it spurred him “to put pencil to paper and design my first boat.”

Pages of Kirby’s 2021 memoir detail his growth as a designer from Torch, the Kirby Mark I with the bright orange topsides, KC 205. His dinghy design practice was in high gear from 1958 to 1971 when he moved away from the 14 to create the Laser. From the prototype Kirby Mark I through to the standard of the Kirby Mark IV, scores of Kirby designs were built in both wood and fiberglass. Bruce is especially proud of Stewart Morris, perhaps the closest that the UK had to an Arthur Knapp or Buddy Melges, winning the last of his twelve Prince of Wales Cups in the Kirby Mark II Encore. With the backing of Jeremy Pudney, a DeBeers Diamonds executive, Kirby put out a new 14 design every two years, finishing up with the Mark VII.

I was fortunate to hear from Tom Price from Annapolis, who was the crew for another renowned 14 sailor, Dr. Stuart Walker. His pictures of Walker’s Kirby Mark IV, the Porsche 911 of International 14s, show an exquisite marquetry of woods on a hull that weighs not much more than an Interclub Dinghy.

When 1971 came, the chapter of Kirby’s 14 dinghy career that eclipsed all others took a new direction with the introduction of the Laser. Born as the “Weekender,” winner of its first cartopper dinghy bakeoff put on by a boat magazine, the design came out of a Kirby desk drawer to become a generational sailing icon. Hundreds of thousands of Lasers later, with all of those boats sailed by Baby Boomers to Gen Z, the Laser represents too many superlatives to list. It was the It Boat for our crowd.

Bruce Kirby, International 14 maestro

Everyone has their Laser story. Nat Philbrick has his taken from the 1972 Youth Championships in Chicago on Lake Michigan. In my interview about Kirby with Nat, he detailed his showing up with his Laser from Pittsburgh, tipping the scales weighing 126 pounds sopping wet and discovering the need for human ballast when the wind blows.

I’ll paraphrase the interview: “In light air, I was at the top the first day. More wind the second day, the middle, and finally heavier air, when I was last…” Nat faced the sobering fact of the need for weight and strength embedded into the performance DNA of the Laser.

I have my own Laser adoption story. I had a rebuilt wooden Thistle, #973, until my freshman year at college when I heard about this Laser, the hot new boat. I was going to be the director of sailing at Mantoloking, a fabled center of Barnegat Bay sailing. Jim Miller, a Thistle champ, was the proprietor of Oyster Bay Boat Shop and was a Laser dealer…the first dealer. With five minutes of haggling, I traded the Thistle to Jim for Laser #1942, in orange. I drove to the Jersey shore with the boat on the roof, with drivers staring at me on the Jersey Turnpike. I arrived at Mantoloking’s pebbled parking lot, rigged up I went out to the Tuesday night races. I led in the first race to the weather mark, but headed downwind and death rolled in 10 knots of breeze in front of my entire sailing class. That’s the Laser Bruce Kirby would have appreciated.

Best selling author Philbrick, who worked for Kirby at One Design Yachtsman, writes in The Bruce Kirby Story (in a foreword that every young sailor should read for its simplicity and its depth), “No one has done more for the growth and popularity of sailing than Bruce Kirby.” ■

Scan to tune into the author’s Conversations with Classic Boats podcast.

Tom Darling is the host of Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.