By Eric Forsyth

The start of this year’s cruise was hardly auspicious; Fiona, my Westsail 42, began at the bottom, or, more literally, on the bottom. She was launched at Weeks Yacht Yard in Patchogue, New York, late on a Monday afternoon. A quick check of the bilge seemed normal, and we all went home. On Tuesday morning, she was resting on the bottom of the travel lift slip with water inside the boat about a foot above the engine. A panicked call from the yard at the start of the workday got me rushing down. Pumps had been dropped into the boat, but they would do no good until the leak was stopped. I splashed my way forward with water up to my thighs. I could feel quite a strong current coming from the head, and it didn’t take long to find a severe leak from a hose on the starboard side. I shut the through-hull valve. Now the pumps would be effective, and by lunchtime Fiona was floating again. The yard workers maneuvered the lifting straps back under the boat and by mid-afternoon she was back on the cradle where she had been the day before, considerably the worse for wear. I never put my finger on why the hose—a one-inch diameter manifold that fed water to the head and wash-down pump—detached. I had done no work on the forward head plumbing the previous winter.

The crew for the first part of the trip: the author, Tim and Neil

The interior of the boat was thoroughly washed down with fresh water and detergent to remove the salt and oily scum. All the lockers were emptied, and the contents strewn on deck to dry in the sun. The 12-volt electrical system had destroyed itself by electrolysis, so the batteries were replaced and the backbone wiring rebuilt. All the electrical components were sent to specialists for rebuilding or replacement. The engine lube oil was recycled several times, and the engine was turned over by hand through several revolutions. The engine then started nicely, but we found the transmission was leaking fluid and had to be replaced by a rebuilt unit. All this work delayed the start of the cruise by five weeks. I decided to skip the original plan of sailing first to Newfoundland and instead head directly for the Azores, as the hurricane season was upon us and it was prudent to get into the eastern Atlantic as quickly as possible. The crew consisted of Tim Jones, a young man from a liveaboard family, and Neil Nash, an experienced sailor who had crewed with me before.

The trip to Flores took 16 ½ days; rather lengthy compared to previous crossings. We had fine winds for the first week, a mixture of reaching and running, but when we were about 600 nautical miles from the destination we encountered a slow-moving high-pressure cell that tracked our course. For days the sea was calm, the anemometer needle resolutely refused to lift off the peg, and we made good about 50 miles a day, much of that due to the Gulf Stream current, I’m sure. Tim learnt how to shoot a sight using the sun, but only after we fixed the sextant. When we came to remove the old sextant from its box, we found it had been inundated by the post-launch flood and the half-mirror was destroyed. After thinking about this problem for a day, I realized that we had a roll of aluminum foil on board which was quite shiny on one side. A little work with some scissors and we had a new mirror, although it only worked for the sun; the reflectivity was too poor to see stars.

Replica of a 1703 Russian frigate, Cascais, Portugal

After a few days at the rather spartan marina in Flores, we moved on to Horta. I touched up the painted Fiona sign on the breakwater wall. I added the date, 2017, to the list of visits, making six altogether, starting in 1986. I also found a sign painted by the Cruising Club of America, which had a cruise in the Azores earlier in the year. One day we took a taxi tour to the caldera, the remnant of the crater of a massive volcano. From there we drove to the lighthouse of Capelinhos, which had been inundated in a volcanic eruption in 1957–58. On previous visits, only the top half of the lighthouse had been visible, poking out of the ash left after the eruption. Now it had been dug out and a visitor center built nearby. For a few weeks we enjoyed a pleasant meander down the Azores chain, stopping at every island. A highlight for me, an electrical engineer, was finding a very early hydroelectric plant on São Miguel, still preserved in original condition. From Santa Maria, we made a four-day crossing to Madeira.

Madeira is a beautiful, volcanic island. We managed to squeeze into the crowded harbor at Funchal and enjoyed its great cultural life. Madeira was very popular with the pre-steam Royal Navy. No doubt they appreciated the fine wine, the climate, and, of course, the Portuguese ladies. One night, there was a wonderful classical music concert at the theater, which is modeled after La Scala in Milan. We also stopped at Porto Santo island for a few days. Its claim to fame is that Christopher Columbus married a local girl there.

The leg to the Portuguese coast, the Algarve, is normally a beat to windward. Thanks to Hurricane Ophelia, however, which was lurking several hundred miles to the northwest, the forecast predicted a fair wind and we had a great reach with 10-12 knots on the beam. After Ophelia passed, the wind died completely and we powered to the coast. About midnight on the night before we arrived, we crossed the sea lane to the Straits of Gibraltar. We had to avoid four ships, the last being a huge cruise liner which passed a mile ahead in a blaze of lights. The loom on the coast was visible long before sunrise. We entered the huge marina at Vilamoura about 10:30 a.m. local time and before lunch we were tied up snugly in a slip, just yards away from a boulevard full of restaurants, shops, and tourists.

We met some old cruising friends who had brought their boat to Vilamoura for winter. Lying just a few hundred yards north of the marina are extensive Roman ruins. There is a good bus service to Faro, and I particularly enjoyed that old walled town.

From Vilamoura, we moved west along the coast in easy stages. Portimao was the center of sardine fishing in times past. Now one of the old canneries has been converted into a museum, and they screened a fascinating film of life in the town in the 1940s. When the trawlers arrived in port, a steam whistle summoned workers to the factory, at any time of the night or day, since it was essential to get the fish in the cans as soon as possible.

The sea caves at Lagos are another unique feature of the coast. I took a ride in a small boat into the caves, piloted by a very skillful helmsman. When a southerly wind developed, we rounded Cape St. Vincent and headed up the coast to Sines. We were trapped there for about ten days by strong northerly winds, sometimes reaching gale force. Sines was a Roman port, and the locals are proud of the fact that Vasco da Gama was born there. Finally, we got a break and made a quick dash to Cascais, near Lisbon, where I left the boat and flew home for Christmas.

When I returned in January, I was joined by new crew, Tom Lohre and Andy Brooks, both veterans of previous Fiona cruises. We spent a few days installing new equipment and stocking up. Then a high-pressure system moved in, bringing strong northerly winds for several days, which was a great incentive to leave at once for Madeira. Within an hour of leaving, we had to tie a reef in gale force winds gusting up to 45 knots. But the boat held together, and we sailed through the night as the wind and seas slowly dropped. The wind direction was almost dead astern, and the wind speed rarely dropped below 25 knots. We crashed through the four-foot swell, but the spray was blown away from the boat, which made for dry sailing. On the second night, the stars shone brilliantly in a clear sky. A waxing moon made the sea look like burnished silver; memorable sailing 300 miles northeast of Madeira.

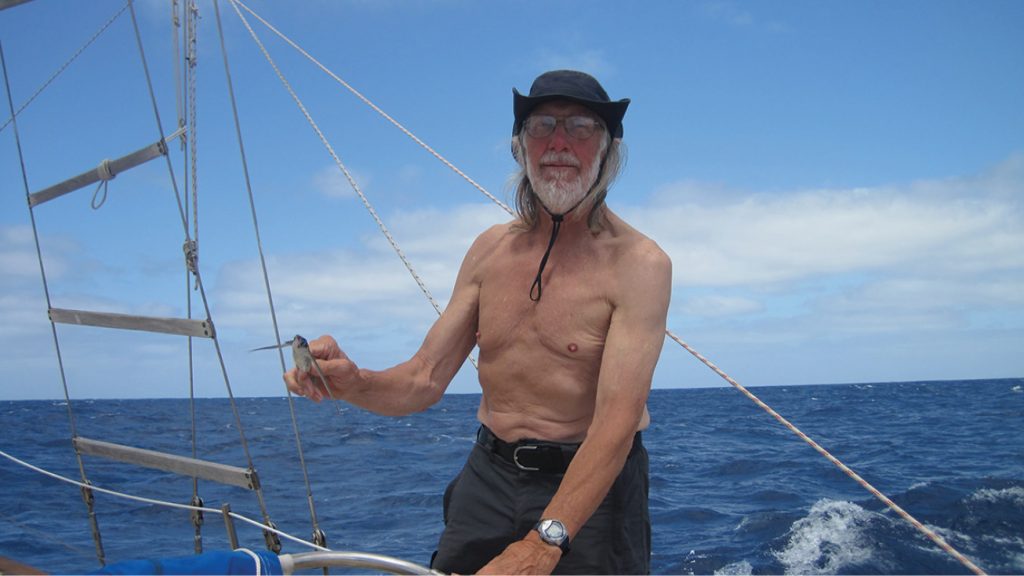

Andy meets his first flying fish.

The next day, we rigged the whisker pole on the port side. The idea was to run wing-and-wing, which would be more efficient than tacking downwind as we had been doing. But the gusty wind caused the jib to flog and threatened its destruction, so we furled it almost right away. The wind continued strong for the rest of the passage. In fact, we made the transit from Cascais to Funchal almost completely under a reefed storm mainsail, and we rarely ventured to set the jib.

The last night, less than a hundred miles from our destination, we passed through a front. The wind almost died for a few hours and we experienced rain, lightning, and a wind shift from northeast to northwest. All this under a brilliant full moon that illuminated the storm-tossed waves as the clouds briefly parted. Then the wind came roaring back with full gale strength. Within minutes the wind peaked at 40 knots, the boat made an unintentional gybe, and all three of us were kept busy sorting things out. We made landfall on the small island of Cima with its welcoming light, and thundered down the coast toward Funchal with a shrieking wind on the starboard. Fortunately, the wind dropped as we headed for the harbor in the lee of a large cape. The only complication was that the mainsail was jammed by a point reefing line wrapping round a light on the spreader, but a violent tug got it free. We tied up at the old stone jetty, thankful to be on solid land.

I enjoyed Madeira again. There was plenty to do, and Tom and Andy had never been there before. Tom, a professional artist, got busy setting down his impressions on canvas. I visited the decaying Victorian edifice that is the headquarters of the Natural Park Service and got permission to visit the Selvagens Islands, part of an uninhabited archipelago lying between Madeira and the Canaries. Before we left, a strong storm produced 60-knot winds in the outer harbor, delaying cruise ships, but we remained safe and snug in the inner harbor. When it blew out, a sail of a little over a day brought us to a small bay on Selvagem Grande, where we attached ourselves to a large mooring buoy.

The next day we dinghied to the desolate shore to be greeted by a game warden and two policemen, who helped drag the inflatable up a ramp. At the warden’s headquarters, the police filled out a form with details from our passports and the boat documentation. We were then free to explore the lonely island. The guidebook mentioned enormous flocks of migratory birds that visit the island and vast number of rabbits on the interior plateau. Andy and I started the ascent of the steep cliff behind the headquarters building. The trail zigzagged up the 45-degree cliff for about a 300-foot vertical climb. I found it rough going. In recent years my sense of balance has deteriorated, and balancing on rough stones with a sheer drop to one side made me very uncomfortable. Andy is an experienced climber and bounded up the path like a mountain goat, delayed only by waiting for me. After about a half-hour we reached the top, where we found a path marked by small stones that led across the interior to a cairn at the north end of the island. The view was desolate. There were no trees, and the ground was littered by lichen-covered stones. A few black lizards skittered about, but we saw no birds or rabbits. We marched across to the cairn, snapped the obligatory photos, and made our way back to the cliff. After a very careful descent we returned to the warden’s place. He told us it was too early for the birds, and the rabbits had been eliminated years ago as they were an invasive species. The police gave us a bottle of beer, which was very welcome. We put the dinghy away, and after a quiet night set sail for the Canary Islands, about 150 nautical miles to the south.

A day’s sail got us to La Gomera in perfect conditions. The next day we wandered over to the largest supermarket in town and laid in all the liquids we needed for the Atlantic crossing: beer, milk, and juice. This was repeated the following day for all the nonperishable food items such as canned veggies and spaghetti. Shopping can be tricky, since shops and services all shut down for siesta between 1 and 4 p.m. Tom painted most days, either in the cabin or on deck if it was not too windy. The subject of his latest painting was Fiona on a stormy, moonlit night. We filled the water tanks, did the laundry, and prepared for a sail to El Hierro Island.

After some deliberation, we decided to head for Puerto de la Estaca at the northeast side of the island. Rumor had it that a new marina had been built. As we approached the island, I was astonished to see several sailboats behind us, all heading for the same destination. This is a bit like seeing several Rolls Royces parked in the lot of a thrift store. Fortunately, there was room for everyone in the new marina, but we had stumbled by chance on a Canary Islands rally of 11 German sailboats, reportedly sponsored by a European insurance service organization. The planners of the marina had never counted on this, and there was only one toilet in the men’s room.

In the morning we caught an infrequent bus to Valverde, the capital. Located a few miles from the coast, it is a steep climb to almost 2,000 feet. The guidebook said the street plan is almost unaltered since Columbus visited on his second voyage, although we found the town without much charm and caught the next bus, three hours later, back to the port. The next day we left for the Cape Verde Islands after lunch. Unfortunately, a disturbance to the northwest drove away the wind and we powered all night, not a good start to a leg that was over 800 miles long.

Things soon changed. For two days, we beat to windward against winds that sometimes reached over 40 knots. Progress was slow, and a prolonged beat is not the nicest point of sailing. We had a problem with a cracked bulkhead carrying the sheaves for the steering cables. The weather continued to be grungy, the wind mostly southwest or thereabouts. We tacked to take advantage of every change in the slant. Wind speed was constantly varying, and we reefed and unreefed as necessary. Ironically, I sailed the same leg, from the Canaries to Mindelo, single-handed in 2013 in about six days. This time it took nine and a half days. Clearly, we had been very unlucky with the wind this time. We picked up a good variety of fresh food at the great public market in Mindelo and set off across the Atlantic, bound for St. Lucia.

Once we were clear of the wind shadow of Santo Antão, which lies to the west of Mindelo, we experienced good trade wind sailing for days; steady ENE winds in the 15–20 range. We reefed the mainsail to keep the boat balanced and engaged the wind vane, which steered much of the time. Andy encountered the first flying fish he had ever seen. Are they flocks or shoals, he wanted to know? We passed the halfway point a week after leaving.

Unfortunately, the wind speed then began to drop and our daily average sank. In addition, the wind veered, so that the rhumbline course became a dead run, not a good point of sailing for the vane. The Southern Cross was visible low on the port side after midnight. We celebrated the equinox as the sun’s declination moved into the Northern Hemisphere. Tom started taking sights to brush up on his celestial navigation skills. On our last night at sea, the waxing moon made a silvery sea as we slipped along, keeping a sharp lookout for coastal traffic. Since leaving the Cape Verdes we had not seen a single ship, but we expected more activity near the islands.

We checked into Rodney Bay Marina, which seemed little changed from my visit in 2012. Each morning we did some maintenance and became tourists in the afternoon. After a few days, we sailed overnight to Saint Pierre in Martinique. The town was completely devastated by a volcanic eruption in 1902 and lay in ruins for decades. It is now coming back to life with shops and a produce market.

The author meets the old seafarer, Vasco de Gama.

We left Saint Pierre at midnight for the Iles des Saintes, a small group of islands lying south of Guadeloupe. This turned out to be a wonderful overnight sail, with a beam wind driving us most of the way. Only in the lee of Dominica did we have to resort to the engine. We picked up a mooring about 9 a.m. at the port of Terre-de-Haut, where we toured Fort Napoleon with its interesting display of 18th-century life in the French army. Pushing on to Antigua, the museum at English Harbour enabled us to compare this to the life of 18th century British sailors. Neither looked very attractive by 20th century standards! In Nevis, where Alexander Hamilton was born, we visited the Hamilton family home, now a museum. After a couple of days there, we made a fast passage to Saint Martin, propelled by strong trade winds.

This is where a note of sadness entered the cruise. Saint Martin and the British Virgin Islands had been devastated by Hurricane Irma in 2017. Many of my familiar anchorages were littered with shattered boats, and onshore shops, houses, and hotels lay deserted and empty. Marinas were scarcely functioning. Even money was hard to get, as ATMs were rare.

We headed north from Jost Van Dyke to Bermuda. After enjoying a pleasant sojourn there, we arrived at Long Island in mid-May 2018, completing my 27th Atlantic crossing. ■

Eric Forsyth made his first transatlantic crossing with his wife Edith in 1964, and they sailed together until Edith’s death in 1991. Eric’s Westsail 42, Fiona, was delivered as a bare hull in 1975 and completed in 1983. He has sailed Fiona ever since.

In the 1990s, Eric rounded Cape Horn and cruised Newfoundland and Labrador. From 1995 to ’97, he sailed around the world. Shortly thereafter he took Fiona to Easter Island and the Chilean canals, and crossed the Drake Passage to the Antarctic Peninsula. He returned home to New York by way of South Georgia, Tristan da Cunha, Cape Town, St. Helena, the Caribbean, and Bermuda. In 2000–01, Eric sailed to Spitzbergen in the Arctic, and from Norway to Scotland, Ireland, Portugal, the Caribbean, and Maine.

Eric completed another circumnavigation in 2002–03. The cruise followed the track of the old clipper ships around the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Leeuwin, and Cape Horn. After an extensive refit, Eric sailed Fiona to the Baltic, Brazil, and the Falklands. His subsequent voyaging destinations have included Greenland, Newfoundland, Labrador, the Northwest Passage, South Africa, and Antarctica.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the 2019 edition of Voyages, the Cruising Club of America’s (CCA) annual publication, and is reprinted with permission. Special thanks to CCA Commodore W. Bradford Willauer and Voyages Editors Jack and Zdenka Griswold.

The Cruising Club of America is comprised of more than 1,300 accomplished ocean sailors who willingly share their cruising expertise through books, articles, blogs, and onboard opportunities. Together with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club, the CCA organizes the legendary Newport Bermuda Race. With active involvement and support from its 14 stations and posts around the United States, Canada and Bermuda, the club focuses significant national and international outreach efforts on ocean safety and seamanship training through hands-on seminars. The CCA’s Bonnell Cove Foundation makes grants to non-profit organizations for projects in safety at sea and environmental protection. For more information, visit cruisingclub.org.