By Anne Kolker

Photos by the author

I had been talking about doing an Atlantic crossing on my boat Etoile, a 52-foot sloop-rigged Stellar, but the complexity of the systems made it seem like a daunting project. When my friend, Margaret “Garet” Wohl, sent me a copy of Cape Horn to Starboard by John Kretschmer, featuring a Contessa 32, I thought the story was compelling. Garet had bought a 1985 Contessa 32 and asked if I would consider an Atlantic crossing with her as part of a crew of three. It sounded like a real adventure on a much simpler boat than mine. Garet and I had sailed together on many offshore adventures and races over the past ten years. Of course, I said yes without hesitation. Garet also asked a friend with whom she had done an ARC race many years ago to join us. He too agreed to come.

Garet had owned Salacia, her Contessa 32, for about six months before deciding to do the crossing. She documented the boat in Denmark for ease of EPIRB registration, then worked very hard to get all systems ready, including adding new sails, a small solar panel, safety equipment, and an IridiumGO! for communications. She took small trips from her home harbor in Sète, France.

Garet at the helm

In late September 2018, she began the journey down the coasts of France and Spain to deliver Salacia to the Canary Islands, from which we hoped to depart in January 2019. In early October, Garet called me to let me know that her ARC friend wouldn’t be joining us due to a heart problem. She searched for a replacement through an online site for ocean crew and found Chris, an experienced 58-year-old British sailor who had done two transatlantic crossings, west to east, and who was, per Garet’s evaluation, a very capable sailor with mechanical skills to boot.

To familiarize myself with the boat, I joined Garet for a two-week trip on Salacia from Barcelona to Valencia. It was small and sturdy. We had a problem with the overheat alarm for the engine, but it turned out to be the alarm, which was old, not the engine, which was new. We had a self-steering wind- vane, which seemed like a good idea, although it was totally new to me. Our Spanish coastal trip was mostly motor-sailing, so we never used the wind-vane.

Salacia on her mooring in Grenada

We planned to depart the Canaries in early January 2019. I arrived in Grand Canaria on January 1 and met Chris at the airport. We shared a taxi to the marina where Salacia was docked and stowed our gear aboard. Chris was clearly an easygoing and capable crew member. After a few days of final preparation and provisioning, we set off for Mindelo in the Cape Verde islands, since there was very little wind to take us west but enough wind to take us south until the butter melts.

We departed on January 3. Once beyond the shadow of Grand Canaria, we had good wind and nice weather with little wave action. We settled into our routine of three hours on and six hours off watch. All was good until 2230 on day three, when I was making tea in anticipation of my 2300 watch. I was pouring boiling water into my mug, but not holding on, when the boat lurched. I went flying backward against a knob, with the teapot in hand. I was able to place the teapot on the nav station desk before I crashed and felt immediately that I had fractured my clavicle. (I am a physician, so I was fairly sure I knew what had happened.) My first reaction was nausea, and then I fainted. I recovered quickly and ascertained that my shoulder, arm, and hand still worked and, aside from intense pain, I was probably not badly injured. I insisted on standing my watch for a while to get some fresh air. Then I tried to sleep as best I could in whatever position wasn’t painful.

The next few days were relatively pleasant, with lots of marine life and occasional ships to watch. Chris and Garet chased a leak that was causing the bilge pump to cycle, which was a concern for battery drain. It turned out that there were two areas of hoses (the engine exhaust and a through-hull vent for the heater) which were not adequately sealed, but easy to fix. We arrived in Mindelo on January 11, navigating into the harbor with gusts to 29 knots at the approach. After docking, I headed for the shower, where I was finally able to see my shoulder, covered in a deep-purple bruise that flowed down to my elbow. I checked some reliable sources to be sure that there was no real treatment for a clavicle fracture. Aside from pain on movement, I was fine while taking lots of ibuprofen.

The author, Chris, and Garet

After adding to our provisions and resting for a few days, we left Mindelo on January 14 for our crossing. Again, we settled into our routine. We picked up the equatorial current for a nice ride, giving us a speed of about five knots. After dinner on January 16, we planned to charge the batteries but the engine wouldn’t start. We measured 4.7 volts on the starting battery. We deduced that leaving the switch for that battery in the “on” position had drained it. Luckily, we were able to jump-start the engine and recharge the starting battery.

On the morning of day five, Garet woke me to come on deck. Chris was clearly not well. He admitted to having chest pain that was similar to what had caused him to have a cardiac stent placed several years before. We knew nothing of this history. Chris had talked quite a bit about biking the hills of the Tour de France, running half-marathons, and doing solo English Channel crossings on his small sailboat. He had seemed like a very fit 58-year-old man. Apparently, he was given a clean slate from his doctor and was taking no medications. I questioned him about his medical history—his father had died at age 60 and a male cousin at age 50, both of cardiac causes—and quickly decided that we needed to have him rescued. His pulse was faint, color was grey, and pain was evident and constant. I immediately gave him two adult aspirin, the only first-line therapy we had for him. It seemed pretty clear to me that he was dehydrated, and his stent, which was in a major blood vessel supplying his heart, was now clotting off.

Chris had the phone contact for the Falmouth, England, search and rescue team. We called them on the satellite phone for help. They patched us through to a physician, to whom I was able to give a cogent history and review of the problem. They immediately agreed to arrange for a rescue by means of a boat transfer. I sent Chris below decks to lie down, drink water, and remain quiet. He was very anxious and clearly uncomfortable, but he declined any narcotic to ease his pain. I was ambivalent about giving him narcotics, knowing there would be a transfer at sea that might require some agility, but I thought it could have helped.

At first, the Falmouth SAR asked us to call out a Mayday, which we did without any reply. We were pretty sure that there were no boats within our radio range. They also asked if we could turn back toward Cape Verde, but with 20 knots of wind behind us and very little fuel, our attempt to return nearly 500 miles would have been futile. We continued on after being told that Frontier Jacaranda, a 292-meter freighter coming from South America toward Rotterdam, would rendezvous with us at around 0300. We began to communicate with the freighter via email, giving our position every few hours. The captain explained his plan to position the vessel so that we would be in their lee for the rescue.

I checked on Chris regularly to be sure he wasn’t feeling worse. I worried that his continued chest pain, despite the aspirin, indicated that the suspected clot was continuing to further damage his heart. I tried to help him remain calm and gave him some information about what he might expect in the coming days. I explained that transfer home to Great Britain was unlikely until he was stable. I gently added that I thought this event would surely diminish his ability to do strenuous exercise, but that his exercise tolerance would be evaluated much later, once he was home and stable. We were both anxious, yet trying to be calm. What I found most disturbing was that Chris was certain that he had never been told to take daily aspirin, which would be the norm for patients with cardiac stents in the U.S.

Finally, at around 0130 GMT on January 18, we hove to, waiting to see Frontier Jacaranda, having already spotted her on AIS. She appeared with all deck lights on, fenders lowered, and crew along the rail. I spoke with the captain, explaining that Chris needed to be picked up in their rescue boat, as had been arranged, since he was unable to engage in any sort of physical exertion. We dropped our sails and motored as close as we dared. The freighter was moving slowly as we came near. The rescue boat was lowered and came toward us with four crew and a huge bag of what looked like two-inch diameter rope. Despite my injured state, I was able to catch the line and tie it to our midship deck cleat while they approached and tied alongside. Chris left us, carrying only his PFD, wallet, passport, and cellphone. We watched briefly as they turned back toward their ship. It was about 0400 GMT. Although we were extremely sleep deprived, we raised our sails and turned west just before sunrise. Now we were two sailors with at least 1,800 miles to go.

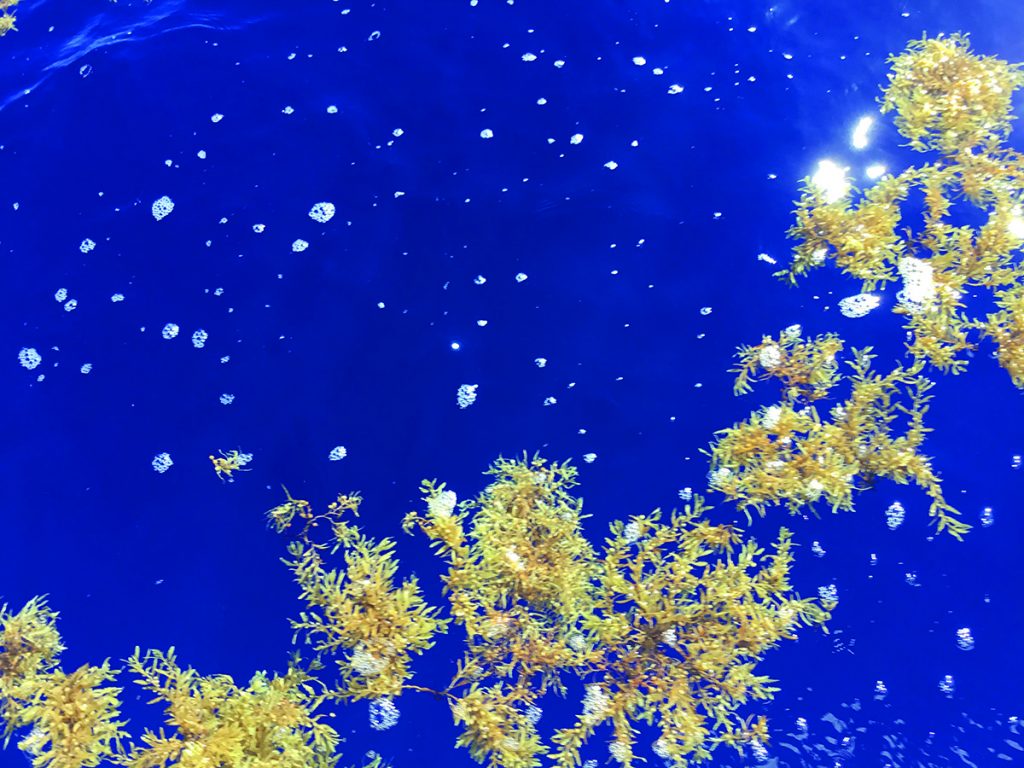

Sargassum, looking beautiful and harmless

The next two-and-a-half weeks were slow. Most of the time, we had little wind (between four and eight knots), clear skies, virtually no rain, and flat, calm seas. We had shooting stars every night and flying fish all day. Sunrise and sunset were the usual beautiful offshore events. The only really overcast day and night, unfortunately, was during the total eclipse of the moon, an event I had been excited to experience in the dark skies offshore. Our routine of three hours on and three hours off was exhausting. We set our phones to wake us every 20 minutes in the night to be sure we didn’t miss an oncoming freighter. Otherwise, we spent our days reading, resting, and fixing things. A low-pressure oil alarm kept sounding off, but it seemed to be another alarm problem, not a pressure problem. To be sure, we contacted the engine company via email. The toilet seat on the badly conceived vacu-flush toilet fell off and needed to be fixed in order to get the toilet to flush.

Each day our weather forecaster seemed to think we were about to have better wind, but it never happened. We sailed on poled-out jib alone and gybed to change course. It required a big effort from me to roll the sail in and out, but with just two of us, there was no other choice. Dealing with the pole was beyond my shoulder strength. As we neared the Caribbean, we struggled with sargassum weed clumping on our wind-vane tiller, which created drag and caused us to veer off course. Ultimately, we were able to push it off with some effort using a boat hook, which we pushed along the edge of the vane. It was a battle lasting several days and nights.

We passed south of Barbados, having decided to make landfall on Grenada, where Garet has a house. I had decided that I would fly home from the first port we reached, so that I could finally get medical attention. We arrived in Grenada’s Prickly Bay just after midnight on February 6. My final job was to make a large loop and lasso a mooring as we came alongside it. It worked on the third try. Finally, we could sleep more than three hours! But first we tied up properly, opened a bottle of wine, and celebrated. It was about 0900 local time when we awoke to get ready to offload.

I flew home on February 7. I was seen by an orthopedic surgeon, who confirmed that my clavicle had been fractured into many pieces. Surgery was not indicated. After several months of rehabilitation and exercise, I am almost back to normal.

Chris is alive. After a two-day voyage on Frontier Jacaranda, he was brought to Cape Verde, where he spent two days in their hospital. He was then air-transferred to Grand Canaria, where he spent two-and-a-half weeks in cardiac intensive care. From there, he was transferred home for continued hospitalization. He received an AICD (automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator) in addition to intense therapy with a blood thinner, probably to protect against further clotting. The last time I heard from Chris, several months ago, he reported that he was starting cardiac rehabilitation. He explained that his functional status was quite limited due to a high degree of heart failure. He thanked me for having told him what would happen, saying that it all in fact happened as I had described it would. He added that his doctor told him that my care had saved his life. It is gratifying to know that he survived. Not knowing what had happened, Garet and I worried every day about Chris.

Garet shipped Salacia back across the Atlantic. I went back to sailing Etoile for the Marion Bermuda Race. I now have a big bottle of aspirin on board. You never know what can happen. ■

Anne Kolker is an anesthesiologist. She worked at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for 30 years before retiring to do more sailing. Anne became an avid sailor when she began sailing about 29 years ago with her husband, Alan. They bought Etoile with plans to retire and cruise, but Alan died in 2008. Since then, Anne has sailed numerous offshore races on Etoile with an all- female crew, as well as serving as crew and ship’s doctor for races on other boats. She has also done many cruises along the U.S. East Coast.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the 2020 edition of Voyages, the Cruising Club of America’s (CCA) annual publication, and is reprinted with permission. Special thanks to CCA Commodore W. Bradford Willauer and Voyages Editors Zdenka & Jack Griswold.

The Cruising Club of America comprises more than 1,300 accomplished ocean sailors who willingly share their cruising expertise through books, articles, blogs, and onboard opportunities. Together with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club, the CCA organizes the legendary Newport Bermuda Race. With active involvement and support from its 14 stations and posts around the United States, Canada and Bermuda, the club focuses significant national and international outreach efforts on ocean safety and seamanship training through hands-on seminars. The CCA’s Bonnell Cove Foundation makes grants to non-profit organizations for projects in safety at sea and environmental protection. For more information, visit cruisingclub.org.