By Tom Darling, Conversations with Classic Boats

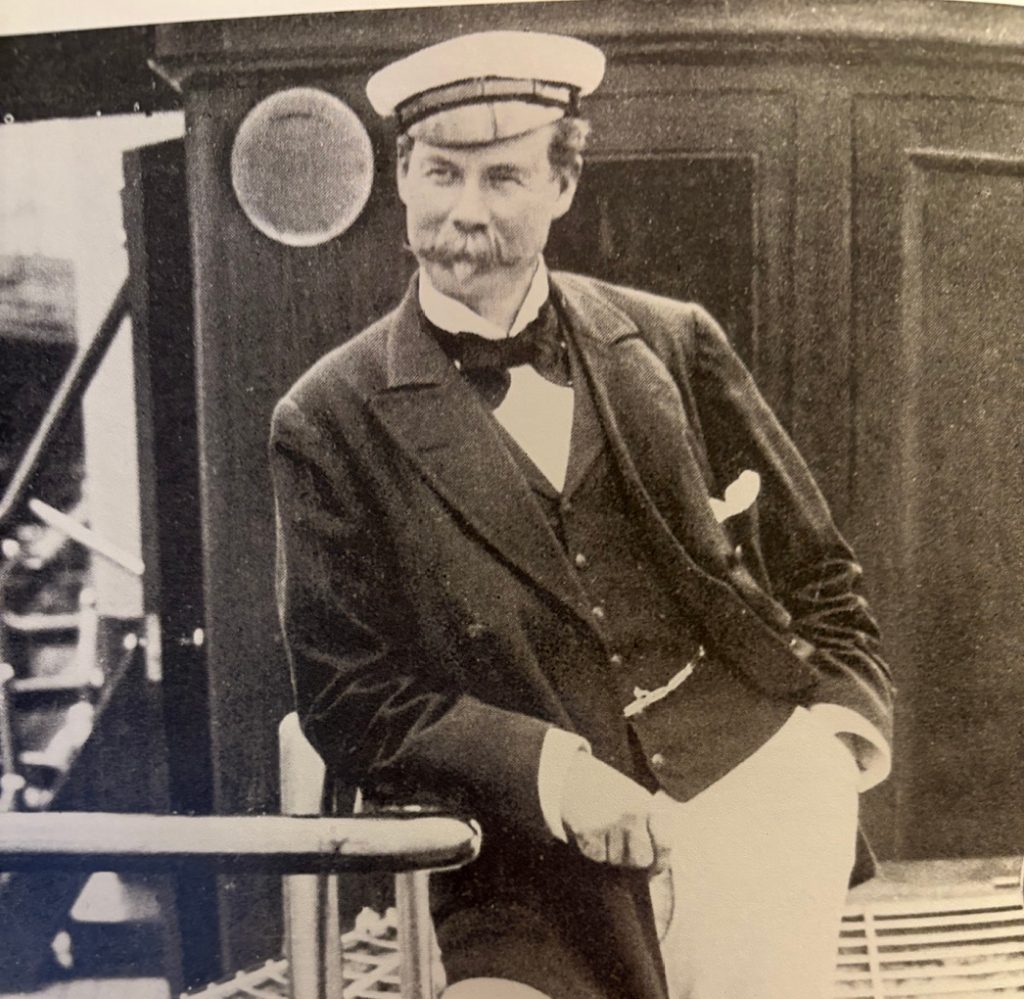

Scottish ace skipper Charlie Barr (right) coaches the owner of Columbia.

Who has ever heard of the Barrs; Captain John Barr and his half-brother Charlie (often spelled Charley)? Captain John steered some of the most famous offshore yachts in Britain and America. Younger brother Charlie, in league with Nat Herreshoff, took the helm of a succession of America’s Cup defenders in the Gilded Age culminating with the mighty Reliance in 1903.

In this issue, we’re presenting original research gathered from the relatives of famous figures like the Barrs. We’ve carried on a dialogue with Alasdair Purves, great-great-grandson of Charlie Barr who has spent years researching a remarkable tale of Scotland’s most famous sailing native son. Alasdair, who describes himself as “now 100% Australian” on his website, is dedicated to telling the story of his family’s sailing ace. He presents that case in a YouTube segment, and is embarking on a speaking tour this fall here in the Northeast. If you can, go and hear him.

The tale of Captain John Barr, a pioneer in Scottish yachting as helmsman, delivery captain and waterman, set the stage for his more famous sibling. John’s career as a “test pilot” for renowned Scottish boatbuilder William Fife and his reputation as a hired gun for Yanks and Brits in America, is a very well-kept yachting history secret. Nevertheless, it is John Barr who’s in the Sailing Hall of Fame.

John died at his adopted home in Marblehead, MA in 1909; Charlie passed in his homeport of Gourock, around the bend of the Firth of Clyde from central Glasgow, in 1911. Together, they were the most sought-after skippering team of the Gilded Age in 1890s America.

We’ll also briefly explore the sailing life and times of another Glaswegian yachtsman, one Sir Thomas Lipton, ambitious and affable challenger for the America’s Cup, five times. Lipton came for the 1899 challenge with his Shamrock and was still racing in 1930, in the era of the J Boats, with his Shamrock V. And he sold a lot of tea in the process.

Valkyrie III off Glasgow

Lipton’s first challenger Shamrock, 1899

A Brief History of the Clyde: The Ocean Liner Ecosystem

In last month’s article, we profiled the Scottish waterway known as the Firth of Clyde and its capital, Glasgow. Both had a transformative role in both commercial and recreational boating. In the late 19th century, advances in propulsion and large-scale shipbuilding created the travel revolution of the ocean liner, a seagoing steamer of 800 feet or greater dedicated to the transatlantic passenger trade.

The growth of the ocean liner industry created in Glasgow as well as in Newcastle (the Tyne) and Cowes (the Solent) fed a shipbuilding boom that crept into every part of life on the Clyde. The technology to build 1,000-foot liners found its way into everyday boat building.

From 1890 until 1940, the growth and glamor of modern liners attracted both well-heeled and migrant passengers who in turn created demand for faster and fancier craft built by the shipyard in those cities. In Part I, we talked about the designers and builders, on the Clyde, notably C.L. Watson and the William Fife family, who produced generations of classic sailing yachts that we so admire. Ocean liners, along with America’s Cup defenders and graceful sailboats, were the trademarks of

the Clyde.

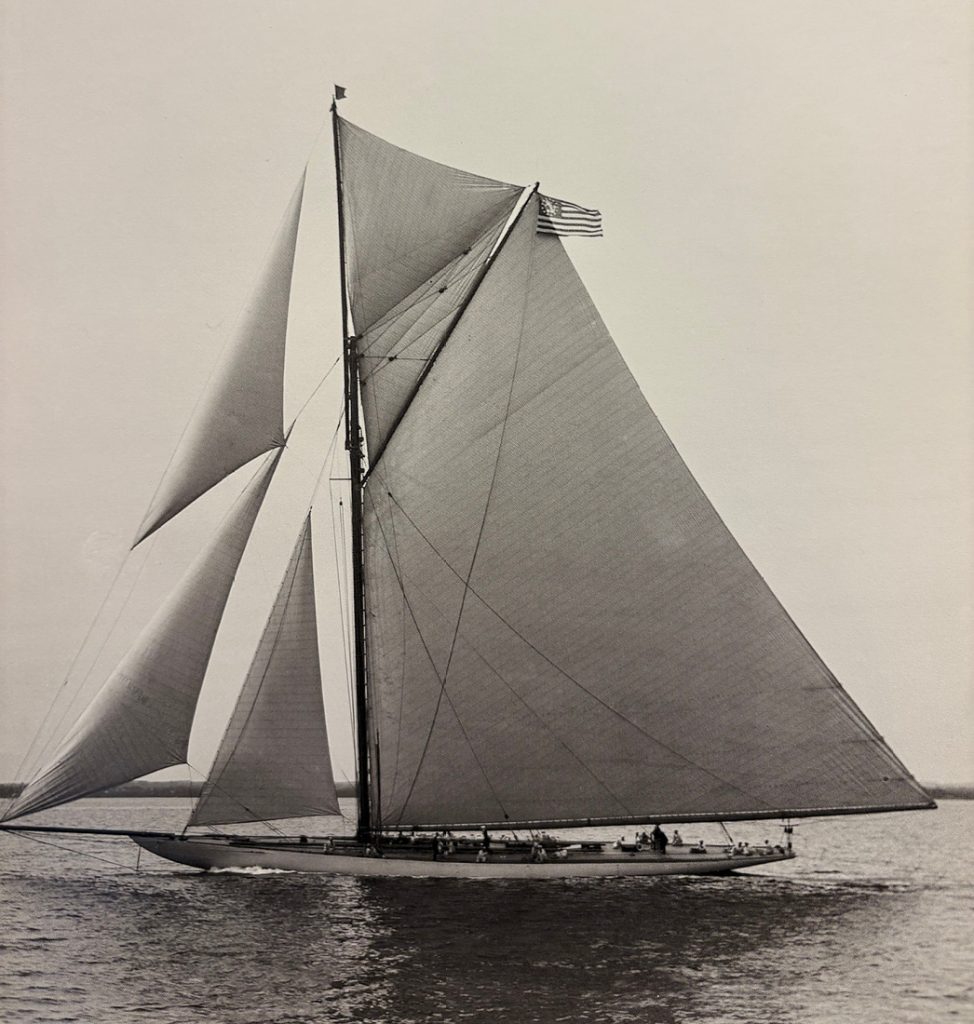

Columbia under full sail, 1899

The Barrs Invade America

The Barrs followed in a long tradition of Clyde watermen, jacks of all trades and masters of their local maritime economy. They built boats, fixed boats, delivered boats, and coached new owners. The Barrs were right at home with smaller boats: their father had a pleasure boat rental business in Gourock on the Firth. Charlie in particular was probably instructing tourists at age 6.

Charlie’s father had multiple wives: the son of his first wife, John paid attention to Charlie They raced the local fishing boats in the informal local races. In gaff-rigged British cutters, Charlie got his skippering experience at a young age.

John Barr had a job testing and delivering boats for the Fife family and C.L Watson. Together the brothers raced the Fife’s Neptune very successfully. When the time came to deliver a Fife yacht to America, in 1882, Charlie was still a teen and commanded a delivery crew to New York. There was work there for a Sottish sailing ace. Boating was in its infancy, with demand for the brothers’ skills.

Returning to the Clyde in 1884, they caught wind of the Royal Northern Yacht Club’s America’s Cup challenge. This was Thistle, a 130-ton design of George L. Watson, one of John’s loyal clients. The seventh challenger was 86 feet long with a 26-foot beam and 8,968 square feet of sail, bigger than their typical assignment. After the Cup, Thistle was acquired and renamed Meteor as part of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s fleet. She would race against the English Britannia, owned by the Kaiser’s uncle, later King Edward VI, each year at Cowes Week. (According to unverified sources, Edward being a more experienced yachtsman and having the faster boat, beat his large and truculent cousin in all races.)

Sir Thomas Lipton, 1899

A derivation of the classic British cutter, Thistle took on John Barr as sailing master and Charlie went along for the ride. Volunteer, the American defender, came from a veteran Boston designer, Edward Burgess (father of Starling Burgess, who would be designer of the 1936 J Boat Ranger). Owned by a Boston team headed by General Charles J Paine, Volunteer was the fast horse of Cup veteran Hank Haff, the Long Island -born skipper or tactician on four defenders from 1881 to 1895.

At the same tonnage, 130 tons, Volunteer measured 108 feet long with roughly the same sail area of 8,981 square feet. She, like few large boats of her time, had a centerboard, not for shoal water but for trim. The first America’s Cup yacht with an all-steel frame and hull, Volunteer easily beat the 1886 defender Mayflower in the defender trials and won both Cup races on September 27 and 30, 1887. As often happened with winning Cup boats, she was bought by a Gilded Age mogul (here John Malcom Forbes) and rerigged as a cruising schooner. It would be years of the Barrs transiting the North Atlantic, moving boats and coaching owners, before they would race Cup boats again.

Charlie and John switch sides

John Barr would go on to captain the entry of one of the most disagreeable challengers in history, the Earl of Dunraven with his Valkyries, in 1893 and 1895. First time around, Dunraven complained about spectator boat wake (remember this racing was in New York Bay, essentially the Atlantic Ocean by Sandy Hook). Despite blowing out her spinnaker in the third and last race, Dunraven without Barr came back in 1895 with a new boat and a demand for a new race course. He was so concerned about the spectator fleet that he requested the match be sailed off Marblehead, not Sandy Hook. The New York Yacht Club America’s Cup Committee denied his request. While Captain John was marketing himself to yacht owners, brother Charlie had taken a somewhat controversial turn, defecting to the American side, specifically to the Herreshoff camp.

Nat, Gloriana and Charlie Barr

Captain Nat Herreshoff liked to provide a turnkey solution for his clients defending the America’s Cup. In between the pressure of biennial Cup campaigns, he was busy designing and building offshore racing yachts, making the sails and staffing the crew for cutting edge offshore boats. One, Gloriana (1891), was such a breakthrough that she defined the offshore boat, with a hull shape that designers emulated for decades.

The half model of Gloriana jumps out in the second-floor display at the Herreshoff Marine Museum in Bristol, RI. She was a departure from the powerful catboats and sandbaggers of the turn of the century and the scow-bowed designs of the Seawanhaka Rule. Early results were excellent, but Herreshoff’s confidence was shaken based on her results against the Scots, John and Charlie. Nat wanted all the weapons on his side, but the Barr brothers continued to beat Gloriana. If Nat could not pry John away, he’d settle for Charlie. He invited Charlie to sail on his Herreshoff boats. Like his older brother sailed for Watson and Fife in the Clyde, Charlie drove for the Wizard of Bristol.

Alasdair Purves reconstructed the narrative of Charlie in the early 1890s: “Think about this 20-year-old being offered a job with the most famous designer in the world. You have just beaten his best boat. Pretty heady stuff.”

Charlie and Lipton: Scot vs Scot

While Charlie was getting the helm of Columbia, Sir Thomas Lipton broke into sailboat racing after amassing an entrepreneurial fortune in grocery stores and tea. Born in 1850, Lipton was an “Ulster Scot,” born in Scotland of Northern Ireland Scottish immigrants. In his mid-teens he moved to America, dabbling in the businesses that would hone his commercial sense. In 1869, he moved back to Glasgow. and worked in his parents’ grocery store which he built into a booming Gilded Age chain. Along the way, he became a master marketer of tea with huge plantations under his command.

While Charlie Barr was becoming a U.S. citizen and driving for Captain Nat, Lipton was becoming immensely rich. Starting in 1899, he began spending that capital on a series of challengers called Shamrock.

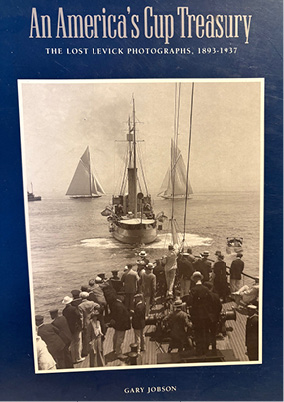

Lipton and Barr were fated to meet in the 1899 Cup series. Charlie was center stage as the defender, Columbia, was the boat to beat. The New York Yacht Club defense was headed by J. Pierpont Morgan, and they commissioned Nathanael Herreshoff to design and build their yacht. At 131 feet, 8 inches, Columbia was about four feet longer than Shamrock. In his book America’s Cup Treasury, Gary Jobson wrote, “Columbia was steered by a recently naturalized American citizen named Charlie Barr who would build a reputation as one of the greatest Cup skippers ever…”

Reliance under full sail

1901: Barr comes through in a pinch

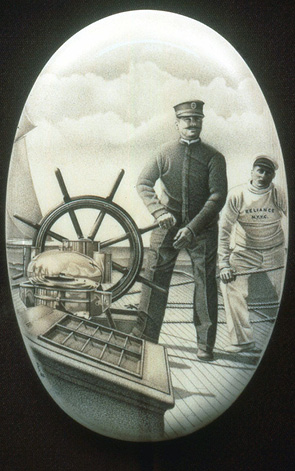

Captain Charles Barr at the helm of Reliance in a scrimshaw by David Smith

In 1901, Constitution was a new boat from Captain Nat and described as a “rocket.” Charlie Barr figured to be the skipper, but through a tortuous political process, he and his crew were pushed aside. He regrouped and piloted a modified and refitted Columbia to that year’s victory. Constitution without Charlie and Columbia with Charlie had dueled all summer. Jobson wrote, “In the final selection trials, the Cup Committee chose Columbia and Barr as the superior package.”

Meanwhile Lipton had commissioned the well-known Scottish naval architect George L Watson to design Shamrock II. “The innovative Watson used a tank to test the hull design, a new standard among Cup designers.” – Jobson. After all the furor, Columbia prevailed in 1901 and Charlie was propelled to the next level in terms of sailing reputation.

Charlie Barr’s last Cup ride was Reliance, felt to be the highest form of the 90-foot waterline beasts raced for the Cup since 1893. The Barrs had driven all of them, challengers and defenders, albeit on shifting sides. The America’s Cup Treasury by Gary Jobson summed it up: “If Reliance was the fastest yacht ever built, it certainly didn’t hurt to have Charlie Barr in command. In the first race of the final match, Barr and Reliance crossed the finish line seven minutes ahead of Shamrock and won on corrected time. The second race was closer but Shamrock and her skipper Bob Wringe failed to overcome Reliance’s handicap.”

This superb book is the definitive work on the first golden age of America’s Cup racing.

Charlie’s sailing style is captured in photos in the aforementioned book, published by the Mariners Museum in Newport News, VA with text edited by Gary Jobson. It features the Levick collection of photographs of America’s Cup boats from 1893-1936. It is marvelous. You can see the pictures of the 1890s defenders as they crept larger and larger toward the massive lines of the 1903 Reliance, 90 feet on the waterline, but stretched to 134 feet overall.

On page 27 there is a photo summarizing Charlie Barr and his intense sailing style, showing Barr peeking over the shoulder of Columbia owner Alexander Cochran. Gary Jobson wrote, “Charlie Barr was the best yacht skipper of his day. He was an intense disciplinarian and spent most of his time at the wheel. All communications to and from him were done through a crewmember standing nearby. Barr was unpopular because he was not a native American and picked a Scandinavian crew, which he personally trained into an efficient unit…”

After 1903, Charlie was less visible on the race circuit. He was recruited to drive the massive schooner Atlantic in the 1905 transatlantic race commissioned by Germany’s Wilheim I, who had caught the yachting bug. The record was set under Barr’s supervision.

By 1907, the illness of his wife and family obligations drew him back to the Clyde, to his hometown of Gourock. Although he did some local sailing, he had perhaps involuntarily retired. Charlie Barr died in 1911 at the age of 49. His great-great grandson Alasdair recounted his visit to the gravesite to “spruce up” the stone. The view of the Clyde is still magnificent, 114 years later. ■

Not a formally trained historian nevertheless a boat storyteller, collecting and reciting stories for the boating curious, Tom Darling hosts Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.

Sources: An America’s Cup Treasury – the Lost Levick Photographs, 1893-1937, Gary Jobson

The History and Evolution of Sailing Yachts, Franco Giorgetti

Interview Alasdair Purves, October 2024-January 2025