Fastnet 100, Opera House 53

By Tom Darling, Conversations with Classic Boats

Golf has its majors, from the Masters through the Opens to the PGA. Baseball has its Fall Classic. Sailing has its iconic races that loom large and provide memories. They generate stories of their own, sometimes for multiple generations. We bring you two classics, one a century, one half a century old, on different continents, with formidable reputations.

The Rolex Fastnet Race’s fearsome reputation is well deserved. Courtesy Rolex

100 Years of Fastnet

This year, the one place for a grand prix sailor to be in 2025 was the 100th anniversary of the Fastnet Race, first sailed in 1925 from Cowes in the Solent to the Fastnet Light in the Irish Sea and returning for the second time to finish outside the UK, in Cherbourg-an-Contentin, France. For every edition previously, the finish had been Plymouth on the southwest coast of England, where Sir Francis Drake departed in 1588 to take on the Spanish Armada.

This Centenary edition was notable for another epic battle on water, the Admiral’s Cup, the team race within a set of races in the Solent, back in action for the first time in twenty-three years. Fifteen teams, many international, of 2-boat pairs, revived what had been in the 1970s through ‘90s the hottest circuit in offshore grand prix sailing. At its peak in the ‘70s, we saw yachts and owners like Morning Club, and Dora-Tenacious driven by Prime Ministers (Teddy Heath) and sailing royalty (Ted Turner). Sailors and gawkers walked the docks on the Isle of Wight where a century before Queen Victoria had vacationed and observed British yachting.

Me and the Great Race

The 2025 Fastnet started with a record =-breaking 444 entries, confirming its status as the world’s largest offshore yacht race. The race also marked the 100th anniversary of the Royal Ocean Racing Club (RORC), organizer of the event. YouTube carried a comprehensive video account of the start and first leg, which I highly recommend.

According to the wrap provided by Rolex online, what made this 2025 Rolex Fastnet Race different was “mild weather, following two stormy editions. The forecast suggested the Azore high extending out toward the British Isles would dominate for the race’s duration, bringing stable conditions but a fully upwind passage to the Rock, followed by a run back.” This was a defanged version of an often ferocious 695-mile race, 59 miles longer than Newport Bermuda

The line honours for the second time belonged to SVR Lazartique, who had among her crew Kiwi Peter Burling of Olympic and America’s Cup fame. Maxis like Black Jack 100, SHK Scallywag and past line honours winner Leopard 3 criss-crossed the English Channel. The first to finish monohull winner, Black Jack finished with a time of 2 days, 12 hours, 31 minutes and 21 seconds, sailing a total of some estimated 750 miles. Back in the pack, Peter Harrison’s Jolt 6 took the overall victory and the historic Gold Cup.

Fastnet 1979

Most of us associate the Race with one time and date: August, 1979, the year of one of the greatest storms experienced in the UK. Masterfully writing in Fastnet Force 10: The Deadliest Storm in the History of Modern Sailing, John Rousmaniere took a world of readers into the midst of sailing in extremis. One of those sailors was me. I had innocently signed on to the crew of a middling S&S 43 for Cowes Week and sailed the so-called inshore races with a crew apparently more interested in their pint than their placing in fleet.

I spent the week close tacking a rock-strewn Isle of Wight beach to avoid current, holding my breath in whirlpool-ridden mark roundings, and having our 14-meter boat crushed upwind by 50-footers or bigger heading up the Ryde shore to the finish. I did almost run down Prince Philip in his Flying 15 whilst motoring up to the mooring post-race; fortunately his longtime crew, Uffa Fox, the godfather of modern planing dinghies, had already died in 1972.

We had nothing to do whatsoever with the 1979 Admiral’s Cup. But I scoured the docks and looked out on the water for some of the top boats. The series consisted of five races with the Fastnet as the final one. Nineteen countries sent teams totaling fifty-seven boats. England was the defender with the former PM’s Morning Cloud and Jeremy Rogers’ Eclipse. The Brits were striking in their designer foul weather gear and dapper appearance. I remember the scrappy Aussies with their lean and mean Police Car; the Irish channeled their national poet, William Butler Yeats, with matching Ron Holland designs, Golden Apple of the Sun and Silver Apple of the Moon, each bearing not just the poetry but a full-color mural on the topsides.

When the time came for the Fastnet we were already a tired, beaten and fast-fading crew. We started without much enthusiasm. When the weather turned foul, we turned and ran. Three hundred boats started in 1979. After a horrific set of wind and water conditions took their toll, Ted Turner and Gary Jobson (Gary seen in an iconic picture steering downwind) won it for Terrible Ted. By the time Dora finished in Plymouth, I was on a Laker Airways no-frills flight to America ($39!). I only learned of the tragedy of the 1979 Fastnet when I landed and picked up a paper with the front page bearing the image of a sailor being lifted to safety. The Fastnet is the most famous race I’ve never finished

Nineteen yachtsmen died in the ill-fated 1979 Fastnet Race, but 75 people were saved by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm crews, and another 65 rescued by lifeboats and shipping. This was the UK’s biggest ever peacetime rescue operation. Courtesy Royal Navy

A Contrast in Style: The Opera House Cup

How many races are known for their parties first and their racing second? With apologies to Midcoast Maine sailors and the Eggemoggin Reach Regatta, advertised as the largest single collection of vintage wooden boats, my award belongs to Nantucket’s Opera House Cup (OHC). The Classic Yacht Owners Association (CYOA) organizes the annual gathering of the vintage fleet for a series of races starting in Newport in June and winding up in Long Island Sound in October. Their website is required reading for classics owners and enthusiasts. The CYOA slots the Opera House Cup. the oldest race, between a weekend in Marblehead and the dual weekend stages of Bristol and Newport. The OHC balloons the island’s population from a crowded 50,000 to a manic 85,000 or more. It’s a maritime Mardi Gras.

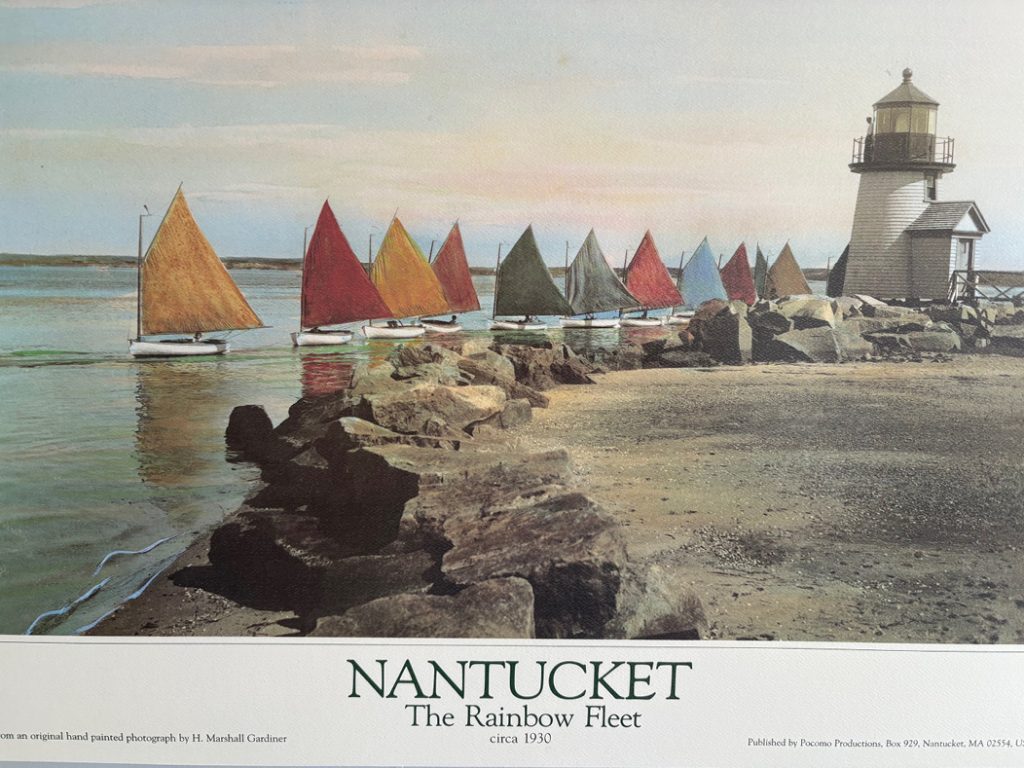

After a heroic sendoff the Sunday morning of the OHC start, there is a parade of sail from the harbor viewed by thousands of shore and boat spectators. The Opera House fleet is accompanied by the local fleet of Rainbows, nee Beetle Cats. Rainbows are best known to tourists for their bright colored and patterned sails. Local artist Marshall Gardiner made them popular with his prints and postcards featuring the mini-catboats silhouetted against the 1790s-built Brant Point Lighthouse. Rainbow owners drag their beloved cats from trailers and docks, backyards and moorings: they have long gone all out to wow the tourists watching the Opera House Cup participants parade out the channel.

Nantucket’s Rainbow Fleet, circa 1930

The other motivation behind the pre-race spectacle and after at the beach party is support of community sailing, specifically Nantucket Community Sailing (NCS). Their mission statement is worth repeating for all of us sailors: “to engage people of all groups in the joy of sailing, offering access to all Nantucket’s youth and teaching every participant in our programs enduring life and leaderships skills, with a deep respect for the marine environment.”

With 150 boats, kayaks and paddleboards, a staff of 35 summer instructors and seven year-round (yes, Nantucket out there near the Gulfstream has a long season), NCS teaches 1,000 children a year and has provided over $1 million in sailing scholarships to island youth. Over the past three decades, NCS has schooled over 20,000 children. My daughter in her college years as an instructor started her NCS kids very young. Today, there is a specific program called “Tiny Salts” for ages 2-4, oversubscribed.

To be fair, the Rolex Fastnet Race is days in open ocean. The Opera House Cup is two hours or so in normally sunny Nantucket Sound in the lee of the island. The risk in the OHC is below the water. There is a reason the island was dubbed the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Sand and shifting sand and boats don’t mix. Four years ago, a misplaced buoy put sand in the way of the larger boats, 50 feet and up. The pileup and mayhem were reminiscent of a Formula 1 car crash on a wet track. Our boat, First Tracks A-26, a 19-year-old Alerion, was the beneficiary of the chaos, skirting the mess and tacking around the unfortunate mark to win the class. The shouting was epic, like an altercation between Viking longships.

The 2024 OHC winners were a modified Alerion sailed by the co-owner of a larger Jim Taylor design that was being sailed by the other co-owner, his wife, and in keeping with real vintage boat tradition, a 1934-built Alden schooner sailed by the owner Lars Forsberg. The fastest elapsed time was turned in by Onawa, a long-nosed, graceful proto 12 Metre done by Starling Burgess. Her elapsed time was 1:35:28, about the time of a Solent Admiral’s Cup inshore race.

Bill Liddle’s Nantucket Alerion has sailed many Opera House Cups.

They race for a quarterboard. The winner of the Opera House Cup receives two carved quarterboards, like those you see over the doorway of virtually every Nantucket house, with the boat’s name. One the crew takes home; the other is enshrined in the offices of NCS. The 12 Metres have been dominant – winners include Valiant, American Eagle, Mariner, Heritage, Weatherly, Columbia, Intrepid, and the pre-war Gleam and Onawa. The Olin Stephens masterpiece Black Watch has multiple boards up on the wall. Other bold-faced names include the schooner Brilliant, designed in 1931 by the very young Olin Stephens that served WWII duty and is today used for sail training at Mystic Seaport Museum.

The 2025 Mystery Course

This 2025 is the first of the mystery course races for the Opera House Cup. Traditionally, the Race Committee assigned one of eight fixed course using government marks in Nantucket Sound. For fifty-two years, visiting sailors have groused about the local knowledge of Nantucket sailors with currents, shifts and sand banks. The limited number of fixed mark courses typically calls for a final beat back from an elusive tetrahedron anchored off the island’s Great Point to the mouth of Nantucket’s breakwaters. Yes, there is local knowledge. I am just personally not sure what it is.

The Opera House Cup fleet of 50-odd boats raced on the third Sunday in August, including wooden vintage boats 20 to 80 feet, a few “Spirit of Tradition” boats (meaning wooden but modern design) along with a handful of Nantucket’s fiberglass International One Design fleet, let in for one race only. The boats depart in a pursuit format, and for years the first off has been a squat Wianno Senior brought over from Cape Cod.

We have gone out to race twenty-five Opera House Cups, nineteen of them in the local Alerion knockabout. A dozen of these 26-foot replicas compete as a one-design class, battling around a 20-mile course, five times their usual in-harbor courses. We have had many battles right to the finish. We can’t wait to see the 2025 new classic course. We hope we find the marks. ■

Wendy Schmidt’s 1935 S&S yawl Santana was once owned by Humphrey Bogart, and this 57-foot beauty is an Opera House Cup contender.

Not a formally trained historian nevertheless a boat storyteller, collecting and reciting stories for the boating curious, Tom Darling hosts Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.