This month we continue our series of what we call gams. That’s a whaling term for conversations, and we’re speaking with the curators of what I consider the most important marine museums in America, if not the world. Christina Brophy is Senior VP of Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, CT, and Evelyn Ansel is Curator of the Herreshoff Marine Museum, the flagship attraction in my old hometown, Bristol, RI.

Christina Brophy

Evelyn Ansel

TD: Hello to both you, and thanks for finding time for a gam.

CB, EA: Thanks for having us, Tom.

TD: Museums are interesting because they’re an art form in a warehouse. They have an ambiance and gestalt of their own. And we all remember going to the museum for the first time. That for me, as a kid, was the Museum of Natural History in New York City – dinosaurs. Over five million people visit annually on the west side of Manhattan, and they walk away with plush toys and books. But most importantly, they walk away with fired imaginations, about creatures that no one has seen for millions of years. I have that same thrill with boats today – classic boats – and with fascinating maritime characters brought to us by the curators of thought-provoking museums.

Christina, you spent your formative years on ocean going research ships, a lot of ocean fauna, Bahamas and sailing. Please tell me about those experiences, and how they sparked your interest in what you’re doing today.

A recreation of Captain Nat’s workshop in the Herreshoff Marine Museum © herreshoff.org

CB: I had one of the most glorious and unusual childhoods I think I’m aware of. I was very fortunate that my brother and I were both raised on a 54-foot yawl named Geronimo, a William Tripp-designed, Abeking & Rasmussen-built, gorgeous dark blue sailboat. My father started the St. George’s School Semester at Sea program on the first Geronimo. We started off really to be a maritime program, just learning about the oceans and marine experience. But he was approached by the National Marine Fisheries Service and others to see if he might want to do some marine biology as well while he had these students aboard.

We would typically take six students from St. George’s, and from other schools in the summertime. We started tagging sharks for the Fisheries Service in the early 1970s, and we were tagging turtles for the University of Florida by the ‘80s. My mother was first mate. My father was captain, although my mother had the same license as my dad and was an incredible mariner in her own right.

We were homeschooled, mostly on this floating school, all over the Caribbean; primarily in the Bahamas, but really the triangle from Trinidad to Halifax to Spain. The Geronimo program, which celebrates its 50th year in 2024 and still running, has tagged thousands of sharks and sea turtles, and this month I’m actually going down to the Caribbean to do some research with my dad. He’s still doing this – he never really retired! He is not with St. George’s anymore, but still working with the University of Florida on turtle research from his own boat in the U.S. Virgin Islands. We lived on Geronimo most of our early lives until we were sent off to boarding school ourselves. Then every summer and every holiday and every chance we had we’d be back on the boat.

TD: So, that’s really a biology background that has morphed over to the artistic side of the world…

CB: Well, a lot of our lives were traveling to far and distant places, and I got very interested in visual culture and a broad diversity of people that we got to know growing up. My grandfather and my father were both very dedicated to the arts, and I figured I’d go to land and learn a bit about visual culture, and the sea would always be there waiting for me when I got back. I was wanted to do a bunch of things like the Sea Education Association (SEA) and some other programs during college, but I got into a bad car accident and wasn’t able to go for a bit, so I took a little detour from that. Going forward, it really was a wonderful way for me to bring all these things together by coming to the maritime museum world.

TD: You made your mark as a creative force at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. And you and I talked about the great Ray Hunt show that you did there, where we didn’t know we were both working on the same subject at the same time. For those of you who haven’t visited the New Bedford Whaling Museum, it’s really a jewel, right up from the waterfront at the fish capital of the U.S.

You came to Mystic Seaport Museum during COVID and navigated through that period. You and I had a collaboration over the Story Boats exhibition, which was really a winner. You are a Rhode Islander relocated to Connecticut. You enjoy sailing a cruising boat with your family in your spare time, and as we learned in 2021, you occasionally duck out for some land sailing?

CB: Yes, we are big fans of Blokarting and you can often see some of our New England Landsailors on the beaches at low tide and parking lots of Rhode Island and Massachusetts in the wintertime zipping around. During our last interview, you recorded me as I was at a Blokarting regatta on a salt flat in California.

TD: Evelyn, you are a Connecticut native moved to Rhode Island. We first met at the Whaling Museum on the island of Nantucket, where you were presenting a fascinating dissertation on Herreshoff and his contributions to modern, just-in-time supply chains. That’s a subject that I have a lot more appreciation for today, and it answered the question for me: “How did Nat build all those boats?” You have a very unique track record that involves digital preservation, which we want to hear more about, but your turf as a small child was really the grounds of the shipyard at Mystic Seaport, was it not?

EA: Yes, that’s correct. I grew up in Mystic and my father worked at the shipyard there throughout my childhood. He was actually there before I was born, and then worked independently for a while, both as a commercial fisherman and then also as a boat builder. He came back to the Museum for the Amistad project in the late ‘90s, but it actually goes back further than that. My grandfather was also a shipwright in the yard at Mystic. He was hired by Maynard Bray in the early ‘70s. My dad was a kid at that time and was hanging around the yard himself. So then, three generations in and out of the Seaport at this point.

TD: Were you crawling around below decks at a very young age?

EA: I didn’t get really sucked in until I was a teenager. I started volunteering in The Boathouse (the Seaport’s boat livery) when I was 13. That was a really fun place to be because it was a great volunteer corps of folks that were a combination of teachers and folks who were retired and kids. It was a really nice group, mixed and intergenerational. I started doing that and then eventually got hired as an attendant and stayed through high school. That was nice, because it was on the Seaport grounds but separate enough from the Shipyard that I felt like I was getting to explore on my own and do my own thing. Sharon Brown was leading the charge at the Boathouse, and there was a really great group of people there at that time.

Some of these boats may become part of Mystic Seaport Museum’s American Watercraft Collection. © Conversations with Classic Boats

TD: Now your expertise is in the area of digital curation, I would say. I see pictures of you, with large documents with large electronic machines doing things. How did you get into that?

EA: Basically, in college I was really interested in art conservation and preservation as a field, and that was actually the direction that I was headed. As an undergrad, I was studying art and art history and chemistry, because those are the three things you need to go off to school for conservation. And because of that, I started working first at the conservation lab at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum with their objects conservator for a summer. And then in the conservation lab at the John Hay Library at Brown, which is the special collections library on campus. As a part of that process, I got involved with something else at the University, the Center for Digital Scholarship. That was a new program exploring what the digital world could do to make collections and archives more accessible to the public.

It sounds very abstract when you talk about digitization, but it’s a very physical process. It’s really hands-on, and having a background in preservation and object and artifact handling is really important when you’re doing high volume scanning of things. And then, it’s a lot of cameras and a lot of time in the studio, although the equipment is still pretty basic.

I will always proselytize for cameras over flatbed scanners for digitization. It’s better for the artifacts and for the institution, especially in medium to small size institutions where you might want to be photographing other things – three dimensional objects as well as flat stuff. Digitization is still sort of a new field. The stuff that people are doing in terms of digital initiatives is not incredibly complicated or that new, at least in the worlds that I’m operating in. But now we’re at this point where digital storage is cheap enough and the equipment is relatively affordable, so the idea of mass digitization – not just reproducing things for your website on a single item at a time basis, but doing large groups of items – has become practical just in the last twenty years.

People have been using digital databases for decades at this point – as long as there have been computers – but I feel like every couple of years we add another layer in terms of the kind of access that can provide. Currently, I’m working in the world where we’re talking about visual access, but as I said, I’m not at the cutting edge of that technology. I’m working in smaller institutions and trying to make collections that historically have not been very accessible, more accessible, because a lot of that equipment, and the methodology, is more approachable than it had been.

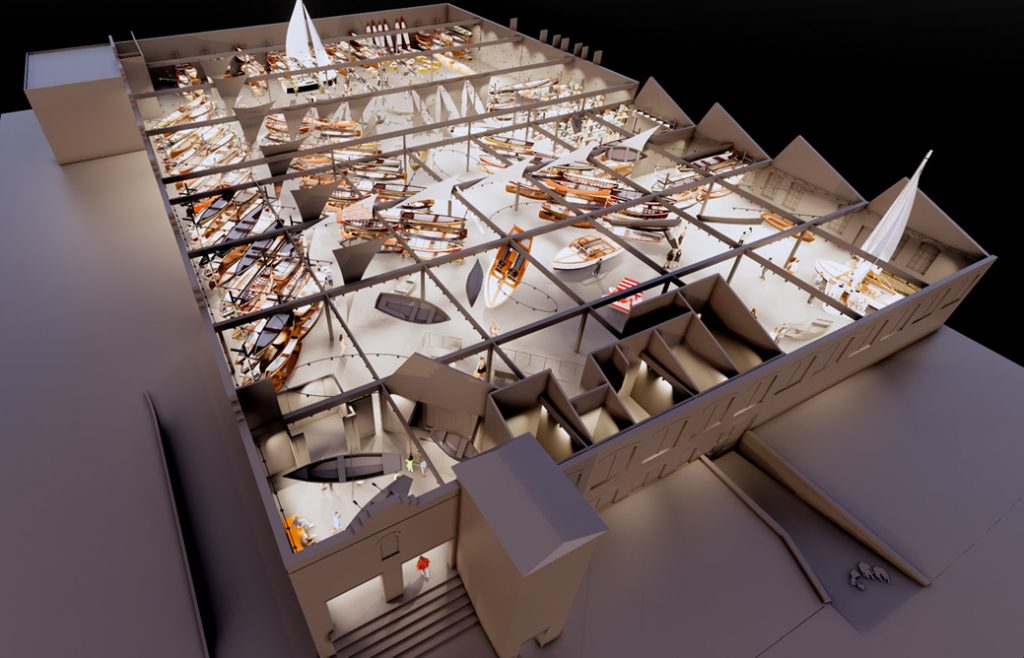

Coming soon: Mystic Seaport Museum’s Wells Boat Hall: Home of the American Watercraft Collection Chris Freeman, VP of Advancement at Mystic Seaport Museum, has allowed Conversations with Classic Boats to explore an immense warehouse building on Greenmanville Avenue that houses a collection that, to date, is only accessible by private tour. Chris shares this news about the Museum’s exciting new project: “Something remarkable is happening at Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic along the banks of the Mystic River. This May, construction will begin to convert 35,000 square feet of the historic Rossie Velvet Mill into public exhibition space to create the Wells Boat Hall: Home of the American Watercraft Collection. Over the past 90 years, Mystic Seaport Museum has amassed a peerless collection of 560 small craft and 250 marine engines, representing two centuries of American Maritime traditions. From a dugout log canoe dating to the 1840s to a Mini Transat racer from 2005, the watercraft collection is a 3D encyclopedia of the American Maritime Experience. Each vessel and engine represents an inspirational story of engineering, design, adventure, exploration, commerce, tragedy and triumph. Mystic Seaport Museum believes that life’s most important lessons can be learned from the sea and that the sea connects us all. Creating a dynamic exhibition space where these stories can be presented to the public will inform and inspire future generations. The 3D rendering that you see here brings the plan to life. Mystic Seaport Museum invites your participation in this project. Please visit us at mysticseaport.org.

TD: I had a guided tour of the new MIT Museum, where they’ve digitized about 1.5 million objects. About how many items do you have in your collections?

CB: That’s actually a very complicated question and depends on how you count certain collections as sets or individual items, for example. We have an excellent research website which does give numbers for groups of collections which can give a sense of the scale of the museum’s holdings, from the Rosenfeld collection of over 800,000 images to 1,650 paintings and prints, 1,600 nautical instruments, 1,150 ship models, 1,700 pieces of scrimshaw, and 100 figureheads, from 1570-present. We also have an extraordinary collection of manuscripts, maps and charts, and over 100,000 naval architecture drawings. Our watercraft collection alone includes over 500 vessels of all shapes, materials, and sizes, some as large as the schooner LA Dunton and some as small as a portage canoe.

EA: This is a tough question to answer on the fly for a number of reasons. It’s often a moving target, and different aspects of a collection get counted differently. For example, museums tend to measure archives in linear feet, not by individual item. Most museums are both accessioning and deaccessioning items all the time, and also in our case, large portions of our collection are still being processed and catalogued, so these are only estimates in our current count.

We have a very small collection by a lot of standards. I looked up our current estimates for various aspects of our collection and here is what they are: Seventy-five boats, more than 500 models, more than 5,000 books and periodicals, around 4,000 prints, photographs and negatives, more than 1,000 pieces of America’s Cup related ephemera, components of Herreshoff vessels, engines and pieces of hardware, and hundreds of linear feet of archival material. We don’t have a good number for this because a lot of our archive is still being processed. ■

Look for Part 2 of my conversation with Christina and Evelyn, in which they will describe their recent, current and future exhibits, in our May edition. Plan to visit Mystic Seaport Museum and the Herreshoff Marine Museum soon. Fair Sailing!

Not a formally trained historian nevertheless a boat storyteller, collecting and reciting stories for the boating curious, Tom Darling is the host of Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.