By Simon Currin, Cruising Club of America Boston Station

Despite being known as the Dangerous Islands, the Tuamotu Archipelago is a South Pacific paradise.

The shrill squawk of our VHF’s Mayday Relay alarm disturbed the predawn peace and shook me out of a deep sleep. We had been sailing reefed down overnight to be certain of making our landfall in daylight. Our watch change was about to take place when the VHF blurted out the spine-chilling news that a yacht was aground on the outside of Raroia’s fringing reef. We were the nearest boat able to respond!

For those that don’t know it, Raroia is a tiny atoll in an archipelago of 77 similar atolls spread over 1,100 miles of the South Pacific. They are called the Tuamotu Archipelago but have been known for centuries as the Dangerous Islands because their navigation can be perilous. Each atoll rises only a few meters from the sea, and traditional charts were notoriously inaccurate. The difficulties are further compounded by swift and unpredictable currents within the passes that lead to their bommie*-strewn lagoon centers.

Sally & Simon enjoying a dive

Raroia was to be our first motu, and we had planned a cautious approach after a 450-mile passage from the Marquesas. All hands were to be on deck for our landfall. We would then eyeball the pass at the time the Tuamotu Tidal Guestimator predicted slack water. If the white water in the pass looked manageable, we would then creep through the pass and use four pairs of eyes to avoid the numerous uncharted bommies between pass and anchorage. The Guestimator is an ingenious spreadsheet (written by the crew of the Ocean Cruising Club’s S/V Visions of Johanna) that juggles known tidal data, latitude, and wind (strength, direction, and duration) to “guess” when to enter Tuamotu passes at slack water. Persistent strong winds driving ocean swells force more water into the lagoons and thus can abolish the flood tide completely. The Guestimator attempts to take all these variables into account — clever stuff!

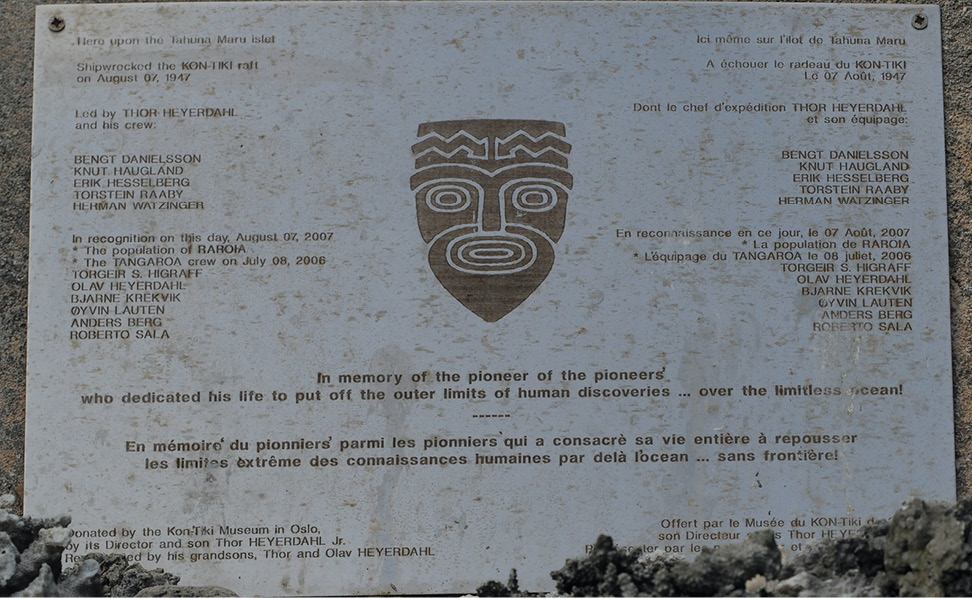

This memorial was donated by the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo.

All our careful preparation was at once undermined when we responded to the Mayday Relay. Despite our proximity, we could not raise the stricken boat, S/V Resolution, on their VHF and instead received messages via VHF and NoForeignLand from vessels safely anchored inside the lagoon. Our sails came down, and we altered course to motor to windward, wondering as we went how we would be able to assist a yacht high and dry on a coral reef being pounded by waves. There were no powerful commercial vessels for hundreds of miles, and we hadn’t the horsepower to pull a boat off a reef even if we could safely pass them a line. Coral atolls are collapsed volcanic seamounts rising steeply from ocean depths, so there would be no possibility of laying anchors and winching off a boat. Lots of thoughts but no solutions flashed through our minds as we raced towards the casualty.

As we closed their coordinates, Resolution’s VHF crackled to life and announced that they had somehow managed to get off the reef and were able to rendezvous with us despite a badly damaged rudder. They requested that we escort them through the pass to a safe anchorage and stand by should their ability to steer usurp them. Dutifully we agreed but did feel like it was a case of the blind leading the blind (and partially disabled) as this was our first landfall in the Dangerous Islands and our first lagoon pass.

Exploring the Wall of Sharks

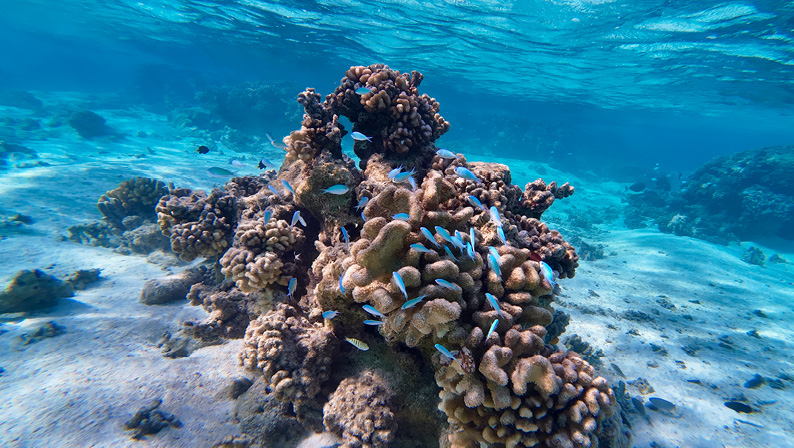

The bommies in Tuamoto attract amazing fish.

Luckily, Resolution also had a Hydrovane whose rudder was relatively unscathed by the impact, and this was able to complement what remained of her main rudder. We were both gingerly approaching the pass when a catamaran, safely anchored inside the lagoon, urged us to come straight in as the current was slack. We wondered about their advice, as it was a spring tide and the wind had been blowing at 20 knots or more for ten days. The Guestimator suggested a midmorning slack water, but we chose to listen to the boat beckoning us in.

Resolution and Shimshal nosed through the first of the tidal white water, and gradually the current increased. Surf was breaking either side of us, and the swirling water was starting to look more like an angry Gulf of Corryvrekan in our Scottish home waters rather than the meek entrance into the tropical paradise we had hoped for. As the current strengthened, we piled on more and more revs until Shimshal was blasting along against both tide and a 20-knot headwind. Our speed over the ground soon crumbled, and then Resolution spun into an eddy and went shooting back out into the ocean at breakneck speed, luckily avoiding the worst of the standing waves as she went. Shimshal soldiered on for a few minutes, but when the engine-overheating alarm came on, we put the helm over and followed Resolution back to the ocean with a speed over the ground of 14 knots.

For the next couple of hours, we drifted around waiting for the midmorning slack that our Guestimator had predicted and wishing that we hadn’t listened to those tucked comfortably up at anchor within the lagoon.

What a difference a couple of hours makes! Our next attempt on the pass found the weak currents we had hoped for, and we shot through with barely a ripple disturbing the surface. By now the sun was up, and so with all eyeballs on deck, we were easily able to spot the bommies and weave our way to a safe anchorage. Our confidence was bolstered by streaming satellite Aquamap images to “spot” the bommies before they could be eyeballed. We switched on our chart plotter’s track function to lay a super-accurate GPS “crumb trail,” enabling us to trace our route back to the ocean should conditions for our exit be less than ideal.

We had chosen to anchor on the eastern side of the atoll, where the reef and palm-clad mini-motus would give perfect shelter from the prevailing trade winds. It was also the place, marked by a memorial plaque, where Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki raft was wrecked in 1947.

Though the seabed was mostly sand, a few bommies littered the anchorage. We used three buoys to “float” our chain so that only a few links of chain lay on the seabed, allowing us to swing without either destroying picture-perfect coral or wrapping our chain around overhanging spikes and crevices. We had procured three abandoned rigid-plastic pearl-farm floats for this purpose, and they were ideal as they don’t shrink and become less buoyant when submerged in the way that a fender does. Each was secured to the chain with some thin cord and a carabiner every 10 meters or so.

Once safely anchored and our “floating” chain suitably admired, we dinghied over to Resolution to meet the crew and inspect their damage. Olaf, the skipper, described the sickening crash that shook the boat when he was thrown out of his bunk as his three-year-old pride and joy fetched up on the coral reef.

In a shaky voice, he explained how he thought his time was up. We dropped over the side with a snorkel, mask, and camera to capture the images that he needed to send to his insurer. Half of the rudder was missing, with the stock protruding but unbent. There were deep gouges to both hull and keel, but the hull was watertight and the rudder useable in favorable conditions — not great to suffer so much damage 550 miles from the nearest haul-out facility, but at least the boat could be sailed.

Tuamoto beaches are never crowded.

Olaf then came over to Shimshal to use our Starlink connection to send all images and documents to his insurers, who swiftly advised him to sail the boat to Tahiti rather than take it out into the ocean and scuttle it, which could so easily have been an option. Resolution’s builder, Hanse Yachts, emailed drawings of the rudder via our Starlink, and they were then forwarded to the Tahiti shipyard that agreed to build and fit a new rudder. Resolving this tricky situation was made so much easier by access to reliable broadband in this remote region of the South Pacific.

I am pleased to report that Resolution made her way without assistance to Tahiti, where we saw her some months later, ashore and awaiting her new rudder.

The ten days we spent snorkeling on Raroia were the perfect introduction to the Tuamotu. The warm water was gin-clear, the coral perfectly adorned with an abundance of flora and fauna. We contacted a speedboat owner in the tiny town on the other side of the atoll to collect a group of cruisers and take us to his home for a feast with music and dancing performed by his mates. Many days in paradise to cherish and remember.

A rock lobster feast about to be enjoyed

Our next motu was the administration center for ten of its smaller neighbors. Children and the sick travel to Makemo for schooling and healthcare. It boasts a population of 815, a fine cathedral, a few shops, a couple of restaurants, and a very warm welcome to visitors. The whole community put on a church fundraising event on Friday night, which a few cruisers attended. A fine feast followed a church service and droves of kids performing music and dancing late into the tropical night.

An Ocean Cruising Club friend encountered one of the other dangers that lurk in the Tuamotu. Having feasted for days on reef fish, she succumbed to severe ciguatera poisoning that rendered her severely unwell for a few days and left her suffering with long-term neuropathic pain, fatigue, and other neurological symptoms. A month later, Niki recorded her firsthand account in an OCC webinar (oceancruisingclub.org/webinars?ID=2738).

Tahanea, some 80 miles farther west, was an uneventful overnight sail with an easy pass to negotiate. We slid through the rushing waters at first light and dropped the anchor in the clear waters of an uninhabited paradise. Once again, we floated our chain and dropped overboard to admire the many bommies from below the water. A short dinghy ride took us back into the pass, where we drifted effortlessly with the current, watching the technicolor corals and marine critters shoot past.

We liked Tahanea’s isolation so much we stayed for a week. A few other cruisers were anchored nearby, which proved lucky as we discovered when our nearest neighbor, S/V Matilda (OCC), retrieved our dinghy at 6 a.m. after it had mysteriously untied itself. It’s always embarrassing to lose a dinghy, but we were relieved to hear how commonly this happens when friends shared their confessions.

We thought we had the perfect window to move farther west. The plan was a slow, overnight 50-mile sail to Fakarava’s South Pass, allowing us to transit at slack water in good daylight. All forecasts agreed that we would arrive at the entrance with wind speeds of less than 10 knots and with flat seas, and we set out with confidence.

Just 15 miles from our destination, things started to go wrong. The wind came out of nowhere, and we thought the squall would soon pass, but it did not. As the wind built, the seas turned white and confused, and our destination looked increasingly dangerous. Fakarava’s South Pass was now an exposed lee-shore, and the prospect of negotiating a narrow tidal pass with 40 knots of wind did not appeal. We altered course to sail 35 miles farther to the North Pass, but the tidal planning didn’t work. To enter at slack water and in daylight, we had to sit out the storm at sea.

Accordingly, we hove to and retreated below to let Shimshal cope with the wind and the angry ocean whilst news pinged in via WhatsApp of the challenging time friends were having in their anchorages in nearby atolls. A hardy couple with circumnavigations and a Northwest Passage transit to their credit came close to losing their boat when their Tahanea anchorage turned into a dangerous lee-shore lashed by 50-knot winds. Many dragged and a few went aground losing yet more rudders to South Pacific coral.

Shimshal rode the waves without drama, and her crew survived without seasickness. By dawn the next day, the winds started to abate, and we closed the North Pass in tranquil conditions. Our OCC friends on S/V Yaghan had been monitoring our progress overnight by AIS and told us of a plumb anchoring spot next to them, which we hurried to and dropped our anchor in 8 meters just off the harbor at Rotoava.

Everyone in the anchorage had been chastened by the storm- force conditions that had caught us all out. Normally the active weather cells in the Tuamotu are on a small scale, but the one that had just passed had been several hundred kilometers in diameter and had developed within a few hours. Its power had been drawn from the sea temperature differential between the deep ocean and shallow water of the atoll lagoons. Nobody had seen it coming, and many had weathered it on unsuitable and unsafe anchorages. Though we didn’t feel it at the time, we were lucky to have been at sea and not in the dangerous anchorage on Tahanea.

Fakarava is one of the most developed atolls in the archipelago, and we were soon ashore enjoying fine food at a harborside restaurant with Anders and Nilla of Yaghan, with whom we have had many encounters during our Pacific passage. The supply ships had visited recently, and unlike many of the other islands, fresh baguettes and croissants were abundant. Even eggs were available if we joined the queue at exactly 7 a.m. on Wednesdays!

Undoubtedly the highlight of our stay on Fakarava was the incomparable diving. We dived and snorkeled both passes and delighted in the appropriately named Wall of Sharks. A magical sub-aqua world.

After a fortnight on Fakarava, we resumed our westward journey, intending to visit Toau, Rangiroa, and Tikehau, but the weather had no regard for our plans. Soon after we had hooked up to a mooring in Toau’s False Pass, we received news of another South Pacific weather phenomenon starting to develop. A squash zone forms when an intensifying region of high pressure snuggles up alongside a low-pressure system compressing the isobars between them. To our south, a vicious winter low was spinning off New Zealand and, farther east, a high-pressure system was forecast to intensify to 1045 hPa. The combined systems were forecast to drive enhanced trade winds with wind speeds of at least 30 knots. With a haul-out deadline looming, we took the advice of John Martin, OCC member and weather forecaster based in New Zealand, and selected a slot to sail to Huahine in the Society Islands before the squash zone had properly formed. Soon all the WhatsApp chatter was of where to sit out the forecast 10-day blow. Our OCC friends S/V Pacific Wind and Matilda, moored next to us, decided to head for Aputaki and a known safe haven. On the evening before our departure for Huahine, Valentine and Gaston, the sole occupants of Toau, barbecued a gourmet supper from freshly caught lobster for four boats.

At first light the next day, Sally and I slipped our last Tuamotu mooring and began a 300-mile boisterous passage to the Society Islands. The squash zone materialized as forecast, and we sat it out in the comfort of a Huahine mooring whilst the winds blew for ten days with gusts to 40 knots.

Our time in the Tuamotu had been truncated by the weather, but our experiences above and below the water of the Dangerous Archipelago had exceeded our expectations. Our enjoyment of these tiny coral specs in the vastness of the South Pacific was enhanced by sharing so many anchorages with a small fleet of fellow OCC boats we had come to know since entering the Pacific. Many of that fleet will be spending the cyclone season in French Polynesia and will resume their onward journey to Australia and New Zealand in 2025. Shimshal is now laid up ashore in the Society Islands, and we will rejoin that New Zealand-bound fleet in 2025.

French Polynesia saw many visitors in 2024.

Cruising Notes

The year 2024 was very busy in French Polynesia, with unprecedented numbers of boats converging there from North, Central, and South America. There is talk of imposing anchoring bans and mandating the use of moorings to preserve coral and prevent overcrowding. However, there appears to be no prospect of increasing the number of moorings, and so there is uncertainty about how cruisers will fare in Polynesia in the years to come. These issues are more acute in the Society Islands, but there are already unenforced restrictions and charges in Fakarava’s Rotoava anchorage and other popular atolls in the Tuamotu.

An expanding cruising population strains the supply of groceries in remote islands where supply ships are sparse, and their schedules sometimes disrupted. Sadly, we did come across some boats without holding tanks who thought it acceptable to discharge their sewerage directly into an idyllic lagoon. Occasionally cruisers would comment on the need to be quick to seize the newly arrived fresh produce, without giving a thought to the needs of the local people — not a great way to endear cruisers to either locals or the authorities.

Electronic charts in the Tuamotu are now super-accurate, and the ability to overlay satellite images via Starlink or building KAP files dramatically improves the safety of navigation within the lagoons. Many blogs (such as S/VSoggyPaws.com) offer downloads of tracks, compendiums of information and KAP files, but don’t forget the OCC has its own database of cruising information shared with the Royal Cruising Club and the Royal Cruising Club Pilotage Foundation.

Simon Currin has been cruising with his wife, Sally, since the mid-1990s, and launched their customized CR480DS cutter, Shimshal II, in Sweden in 2006. After several seasons exploring Scandinavia, they returned to the Scottish Hebrides for five years before departing their home waters in 2015. Their three summers in Greenland were written up in an earlier edition of Voyages as were their exploits in the Canadian Maritimes and New England. Since Simon retired as a physician in 2021, they cruised the Caribbean, and in November 2023 they transited the Panama Canal. Simon joined the Cruising Club of America in 2020 and was the commodore of the Ocean Cruising Club between 2019 and 2024.

*Bommie is a British term forand outcrop of coral reef that is higher than the surrounding platform of reef, often resembling a column and partially exposed at low tide. This story originally appeared in Voyages, the Cruising Club of America’s annual publication, and is reprinted with permission. Special thanks to CCA Commodore John R. Gowell and Voyages Editor Dan Biemesderfer. The Cruising Club of America comprises more than 1,300 accomplished ocean sailors who willingly share their cruising expertise through books, articles, blogs, and onboard opportunities. Together with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club, the CCA organizes the legendary Newport Bermuda Race. With active involvement and support from its 14 stations and posts around the United States, Canada and Bermuda, the club focuses significant national and international outreach efforts on ocean safety and seamanship training through hands-on seminars. For more information, visit cruisingclub.org. ■