By Alex Robinson

Every adventure has at least one moment – a moment that sinks in and will forever connect you back to that time and place. These moments have a way of being small and perhaps inconsequential to other people, but I think you will appreciate this one.

Threshold crew: Steve James, the author, Karyn James, and Sheila McCurdy

It was sometime on the third or fourth day, somewhere in the northern Atlantic off the coast of Portugal. I was off watch, lying in my bunk, listening to the sound of water rushing past the hull. Not necessarily going somewhere, but just going. And in that moment, I could have kept sailing forever.

That was it – that was the moment. But it didn’t start out like that.

It started with me waking up to Threshold rolling around in some Mediterranean swells as we left Alicante, Spain. I am jet lagged and perhaps hung over from the two glasses of wine I had last night at dinner. Karyn James serves muesli for breakfast. She starts me off with a small bowl after seeing me wince when she asks if I am ready to eat. The thought of the soy milk I happily put in the basket on our provisioning trip yesterday is now making my stomach turn. I eat half a bite before thinking better of it and setting the bowl down to warm in the sun and taunt me. I think to myself, how am I going to do this?

I lie down in the aft part of the cockpit. An hour later, after a nap in the sunshine and fresh air, I power through the now-warm muesli. Okay, I can do this.

The next thing I know, Steve James declares that it is time for “tensies” and brings out a bag of pastries. I have two thoughts. One, I will throw up if I eat that right now. Two, I see why my dad, a pastry aficionado himself, likes this guy.

I wake from a long nap in the evening to learn that the AIS is broken. I sit at the computer, click around, press some buttons, and it is fixed. Steve breathes a huge sigh of relief and says, “You’re hired!” A couple of weeks ago, before we knew each other, Steve asked by email for my experience and “any special skills.” At the time, I came up with very little. I have been on sailboats my whole 30 years of life but had nothing on three Cruising Club of America members – until now. I didn’t know that the ability to troubleshoot computer problems counted as a “special skill,” but now I breathe my own sigh of relief, thinking that my excessive napping, queasiness, and inexperience will all be forgiven.

The next morning, we are motoring. We motor all day. Sheila McCurdy [past Commodore of the Cruising Club of America] prepares the first of many happy soup lunches, and I have my first stint in the galley making my favorite expedition meal of gado gado, a dish of noodles and peanut sauce, for dinner. The seas are calm. I feel good, but fear this easy time is fleeting.

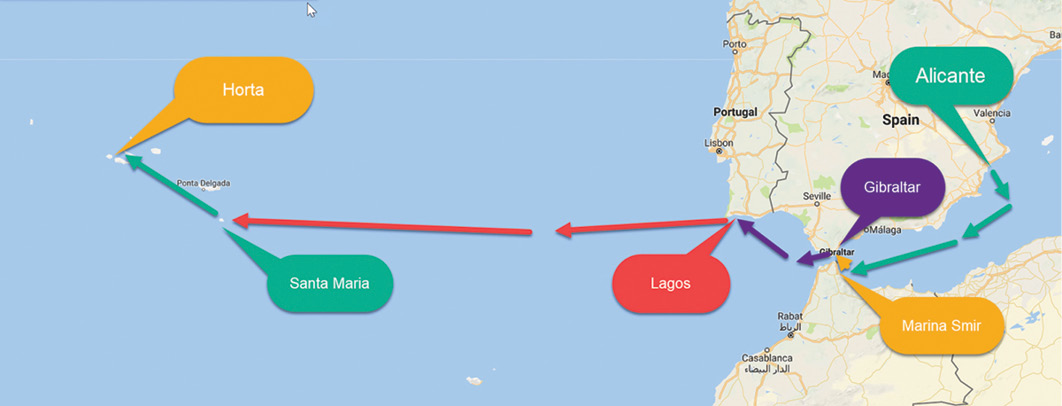

The route brought the author and her shipmates from Alicante, Spain though the Strait of Gibraltar and westward to Horta in the Azores.

On this first leg, we are headed toward Morocco for a small adventure and detour on the way to the Azores. It is a warm-up for the big crossing, which will be my first time sailing directly away from land and into the ocean. It will also be my first time sailing continuously for more than 48 hours. I am excited and a little apprehensive.

Just a month earlier, my boyfriend Chris, my father, and I sailed 32-foot Bluejacket from Norfolk to Boston. It was the last piece of Chris’s and my move to Boston, and our first time sailing through the night and in the ocean under my command. I don’t have a journal from that trip – hell, I don’t think we even made any logbook entries. We ate ham biscuits, we reefed, we steered continuously, we reefed again, we slept for one hour and 40 minutes at time, we called a buddy boat we met along the way every few hours, and finally, we slipped into Newport Harbor at first light.

It was on our stop in Newport that we met up with Sheila, and the idea for me to fly to Alicante three weeks later to help Steve and Karyn sail Threshold to the Azores was born. I wasn’t easy to convince in the moment. But Sheila told me that if I woke up the next morning still thinking about the idea, I should come. And the next morning, I did wake up thinking about it. So here I am.

Crossing the Strait of Gibraltar

It is the middle of another night shift, headed toward Morocco. Steve and I are dodging ships under power. It’s a game of Frogger, getting across a shipping channel that is clearly marked by the constant flow of ships in both directions on our AIS. Steve calls it I-95. We duck right behind one tanker as he passes us, and he toots his horn – in a friendly way; as friendly as a tanker can be, I guess. He is happy that we saw him and gave way. We are now one less small vessel for him to worry about as the radio sounds pan-pans at least every hour, warning of the rafts full of 20, 30, or 50 people in the straits, trying to cross from Africa to Europe.

Without having much chance to sleep, it’s time for Steve to come back on watch with me. We talk about his career as a pilot; he naps; I watch the bearing and range on some unidentifiable lights. Lightning flashes around us, and we steer away from the weather approaching on the radar. It turns toward us; we change course again. We feel a few drops of rain but mostly avoid the thundercloud. It is a fun, fast watch, and tonight I learned that having a variety of reliable tools and a working knowledge of how to use them makes it much easier to make good decisions. But I am also excited to wake up Sheila and retreat to my bunk for my long-awaited 6–10 a.m. sleep. I wake up to Steve fixing eggs and toast for breakfast as we motor toward Morocco, which is now in sight. All hands are on deck this morning for the last stretch toward Marina Smir. The wind comes up and we sail again. Karyn and I are chatting and forget to trim sails, until Steve points out that we are only going five knots. I’m not quick enough to retort that five knots is pretty good for me and Bluejacket, and instead start asking sail trim questions. This kicks off a lesson from Sheila: the main usually luffs at the top first; the jib lead should line up about 60 percent up the luff; adjust your headsail first; it’s okay for the top telltale to flick; adjust your batten tension ahead of time; cunningham flattens sail; okay for foot to bag; carry billow in luff of sail temporarily to depower…I try to absorb it all like a sponge.

Morocco

We make landfall in Morocco at Marina Smir, which precipitates a mad rush to check into customs, hop in a cab, and see the town of Tetouan. I have only known Steve and Karyn for a couple of days, but their energy to run around and explore on land is striking. Jet lag is no longer a reasonable excuse for me, and I realize that Karyn, truly, is an Energizer Bunny. It makes me wonder if they were always like this – or if anyone can develop this adventurous pace and attitude by spending much of their time traveling and discovering new places? If so, I want to be like them when I grow up.

In the old town of Tetouan, we get ensnared in a scheme by a few entrepreneurial locals. They are uncles, cousins and brothers who manage to orchestrate a tour of the town, a showing of rugs, and a dinner out which we never agreed to, but nevertheless went along with. It all ends well with a couple of rugs sent to Sheila’s house, a delicious couscous and tagine dinner, and some good memories of the time we got knowingly scammed on the streets of Tetouan.

The next day we cross the Strait of Gibraltar. I take over steering Threshold from the autopilot for the first time. It is a perfect sail: 20-25 knots of wind on a beam reach, nine knots of boat speed, and sunshine. We dodge ships under clear, blue skies and the stately Rock of Gibraltar.

Gibraltar

In the town of La Línea, we find our way to a local hot spot for dinner, where we order tapas in questionable Spanish and drink wine. The next day, the girls tour the Gibraltar Nature Reserve while Steve cleans out a crystallized head out-take hose. It is a little unfair…until one of those monkeys he warned me about at the top of the Rock jumps up on my head. At which point, I would have taken the head hose.

The author with a new friend in Gibraltar

That night, Steve and Karyn invite friends from the Mediterranean single-sideband radio “net” over for a drink. It’s an exciting encounter, because Sondello and Threshold have been sharing cruising plans and stories for years over the net without ever meeting in person until now. Sheila and I throw together “dinner Threshold” from last night’s Moroccan leftovers and help host an impromptu dinner party.

The next day, we run errands in La Línea – including three bakeries plus a stop for churros and chocolate – and spend the afternoon trying to resurrect the old SSB in order to get weather downloads. Eventually, we give up, grill chicken, and prepare to leave the next day for Lagos.

On the passage to Lagos, I sleep a lot and feel a bit queasy again, but try to pull my weight by doing dishes and standing a long watch motor-sailing the next day. These one-night passages are exhausting, especially for Steve and Karyn, who don’t sleep well at first. I look forward to getting into a rhythm on the longer passage to the Azores.

Lagos

We arrive in the bustling beach town of Lagos and get to work on last-minute passage preparations for the next two days. We have wonderful dinners in town and get a cool tour of the snazzy Sopromar boatyard. But the impending passage is becoming more real and the mood reflects it. We are provisioning with greater purpose and swiftness; tackling boat projects with seriousness; and checking weather reports frequently.

The night before we leave, I am excited, but also quite nervous – mostly about being seasick and tired and potentially having rough weather the whole way. Beating to Lagos was exhausting. But now it’s time to sleep.

Day 1.

We depart Lagos in the early morning and motor through fog and glassy water. We cross a huge pod of dolphins that swim alongside and dance and jump below our bow for minutes on end before sending us off toward the Atlantic Ocean and turning back behind us in our wake. I think to myself, dolphins are a good omen, right?

Ahead of us the water changes from glass to a darker shade, indicating the line of wind that we expect to be blasting down the coast of Portugal and that will hit us when we leave the lee of the land. We raise sails and assume the starboard tack that will take us nearly all the way to Santa Maria.

A few hours later, we have reefed and suited up for rough weather and head into the night. Off watch, I want to take a video selfie to share with Chris later, but I am too queasy to pull out my phone, and don’t know what I would say – here I am, this is it. I know I will regret it later, but I roll over and go to sleep instead.

On watch with Steve, he says this is pretty rough weather for them, and I feel good that it’s not just me and my inexperience that thinks this is rough. A few hours later, I discuss the same topic with Sheila, and she says, “This looks like the North Atlantic to me, pretty typical.” And I wonder to myself if I will ever do this again.

Day 2.

I manage to take a couple photos of the waves; Sheila encourages me to. She’s right – they don’t look as big on camera. She also suggests that I take off the autopilot for a while and steer to feel the waves. We don’t get to that today. I’m still getting used to this difficult, never-ending motion. From the aft cabin on the port side, I watch the ocean rise and fall and rush along the deadlights when a wave pushes us farther over. We are going fast – 9 or 10 knots. The water curls up around the deadlight and then rushes off behind us. It looks like a window into a washing machine and becomes mesmerizing in a way.

The head is all the way forward and faces the port side. I am good at hydrating and therefore make frequent trips forward. The seat lid crashes back down on my spine every time I sit down. Soon I learn to pre-empt this by pulling the lid down to rest on my back immediately after sitting down. Learning to pee in harmony with Threshold and the ocean, I feel a small sense of comfort and mastery. I still can’t stay below long enough to help cook a meal. I do dishes to try to make up for this, and then after each small stint in the galley, I spend 30 minutes lying down in the pilothouse to recover.

On a night watch, Sheila tells me of the beauty she sees in the green waves, the way the moonlight on water takes her breath away, the way that she has learned a lot about a lot of things, but the most about people, and how they think, through sailing. I hear her and admire her passion and love for this. I start watching the waves and get drawn into them. I see the stars and moon and appreciate when they are bright and that there is something to look at during the night. But I am also still queasy, and nervous, and out of my element. I can see the beauty in all of this but don’t feel it. I worry a little if I ever will…maybe this just isn’t for me.

But between the waves are those seconds when I think how neat it is that so few people have been in this exact spot in the world – how the oceans are such a large part of our world. I had never before thought of sailing as a way to see this wilderness, but I start to enjoy and look forward to my trips out of the pilothouse to take a look around at this seascape. Sometimes it looks the same, but every time it is moving, mesmerizing, alive, blue, and scary. And then at night the world turns upside down and the stars come alive. We have a quarter moon, bright as a spotlight that lights up a swath of ocean off our stern, reminding us where we have been and ushering us forward.

Day 3.

I am losing track of time. The wind and waves have lightened, there are no longer any ships within 30 nautical miles, and I feel rested and well fed. For the first time since we left Lagos, I find time for reading and writing and thinking. I am learning so much – not in the organized, linear way that I am used to, but through practical, hands-on experience and osmosis. I am getting more sailing lessons from Sheila and tips for keeping a boat running from observing Steve and Karyn. My journal is full of pages of notes on these things. There are diagrams of wave heights, true and magnetic compass bearings, sail trim, celestial navigation concepts, and surface charts. There are lists of tricks to remember and ideas to implement on my own voyages.

And then it happens, sometime on the third or fourth day, somewhere between Lagos and the Azores. I’m off watch, lying in my bunk, listening to the sound of water rushing past the hull. Not necessarily going somewhere, but just going. And in that moment, I could keep sailing forever…

Day 5.

Land ho! I spot Santa Maria at 1429 GMT. We are motor-sailing for the first time since leaving Lagos five days ago. It is sunny, calm, and the waves have stretched out into gentle, long periods. Many hours pass before we make landfall in Vila do Porto. We finally slip into the small fishing town in the dark and tie up at the end of a dock at 2230. We break out beer, cheese and crackers in the cockpit.

I feel a bit of relief and pride, but mostly happiness and contentment. At times, this journey was so slow and I thought the rolling would never end and it was depressing. But now I wish there were more time – more time for routine, for cooking and reading and learning and mastering. At least this nighttime arrival allows the solitude and camaraderie of the passage to last a little longer.

Santa Maria

We tour Santa Maria the next day, ending with a night out watching the local air traffic controllers cover American rock songs and jam out. Steve and I pull Karyn away from the action around 2300 and head back to Threshold. We leave the next morning for our last leg to Horta. I will miss this. It has been three weeks of pushing limits and doing things I didn’t think I could: staying up all night, getting used to constant motion, eventually staying below to cook without feeling nauseous.

Landfall in the Azores

There were moments of complete discomfort: lying in my bunk not able to do anything, not wanting to take photos or write or read, wondering why the hell people do this. There were moments of dullness: opening up grib files even though they hadn’t changed, staring at the chart plotter even though there were no ships around and only one way to go. There were moments of brilliance: a delicious warm chicken and rice dinner, a whale sighting, a bright moon, a good cup of tea in the middle of the night.

And then there was the moment I realized it was almost over, when I had to leave my bunk, the boat, and, most of all, the crew and our routine – morning coffee, loading our packs for trips to town, crowding around weather files, tackling boat tasks, planning meals, dining out in new places, getting underway, falling into a watch rhythm, and sharing a celebratory beer. I will miss this little ecosystem, but I am excited to build my own version of it back home, with my own boat and crew.

Flying back to Boston, I realize the passion, energy, and love for offshore sailing, adventuring, and remote places that Sheila, Karyn, and Steve have are mature views. We all start somewhere and have the experiences that allow us to develop mastery and passion. It starts from a seed – a role model, a dream, a nudge to come on an adventure – and then there is one moment, and then another, that we choose to follow that sparks the fire.

Sheila at the helm

Alex Robinson resides in Boston, MA with her boyfriend Chris Coulter and their 32-foot sailboat Bluejacket, a 1983 Morgan 323 designed by Ted Brewer and Jack Corey. Alex grew up sailing on her parents’ Valiant 40 and racing dinghies in the Chesapeake Bay, San Francisco Bay, and Puget Sound. She taught small boat sailing in Seattle and the San Juan Islands and crewed on the 62-foot yawl Carlyn and other boats in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. Before relocating to Boston, she spent many weekends exploring the coast of North Carolina on Bluejacket. Alex has a Ph.D. in economics and works at Analysis Group.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the 2018 edition of Voyages, the Cruising Club of America’s (CCA) annual publication, and is reprinted with permission. Special thanks to CCA Commodore W. Bradford Willauer and Voyages Editors Jack and Zdenka Griswold.

The Cruising Club of America is comprised of more than 1,300 accomplished ocean sailors who willingly share their cruising expertise through books, articles, blogs, and onboard opportunities. Together with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club, the CCA organizes the legendary Newport Bermuda Race. With active involvement and support from its 14 stations and posts around the United States, Canada and Bermuda, the club focuses significant national and international outreach efforts on ocean safety and seamanship training through hands-on seminars. The CCA’s Bonnell Cove Foundation makes grants to non-profit organizations for projects in safety at sea and environmental protection. For more information, visit cruisingclub.org.